2025

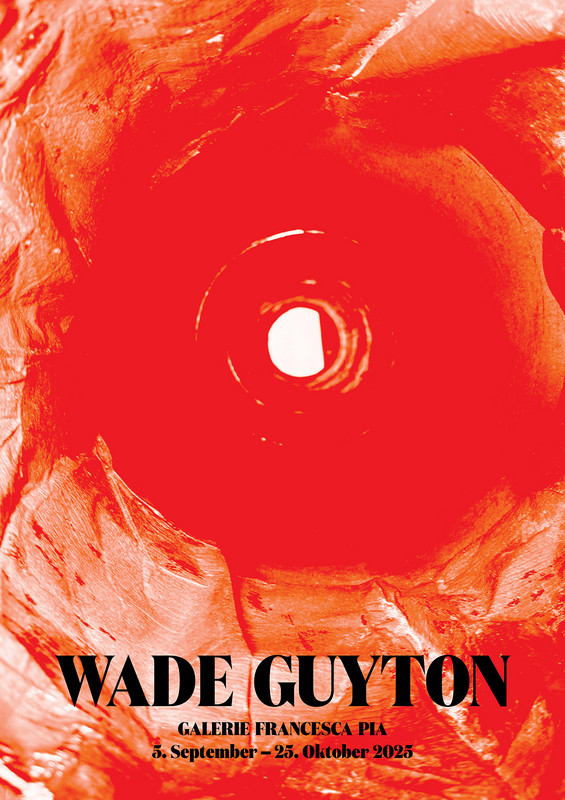

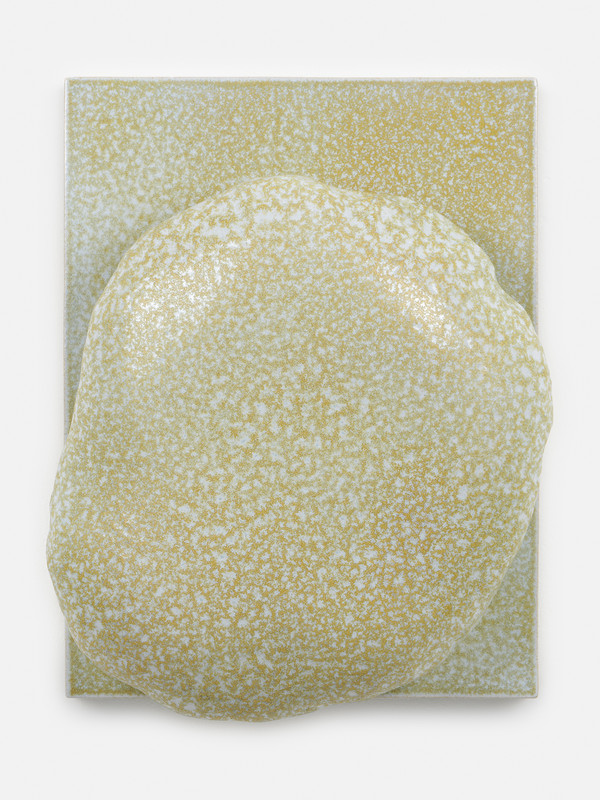

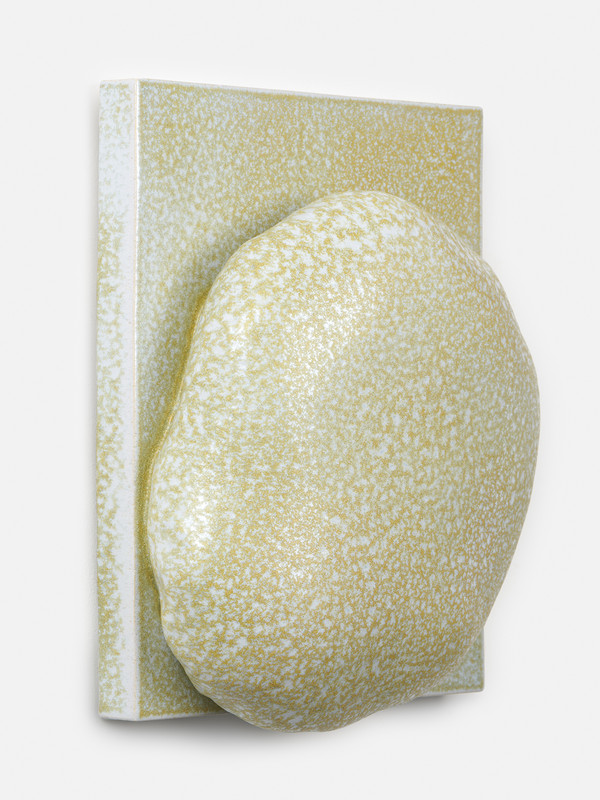

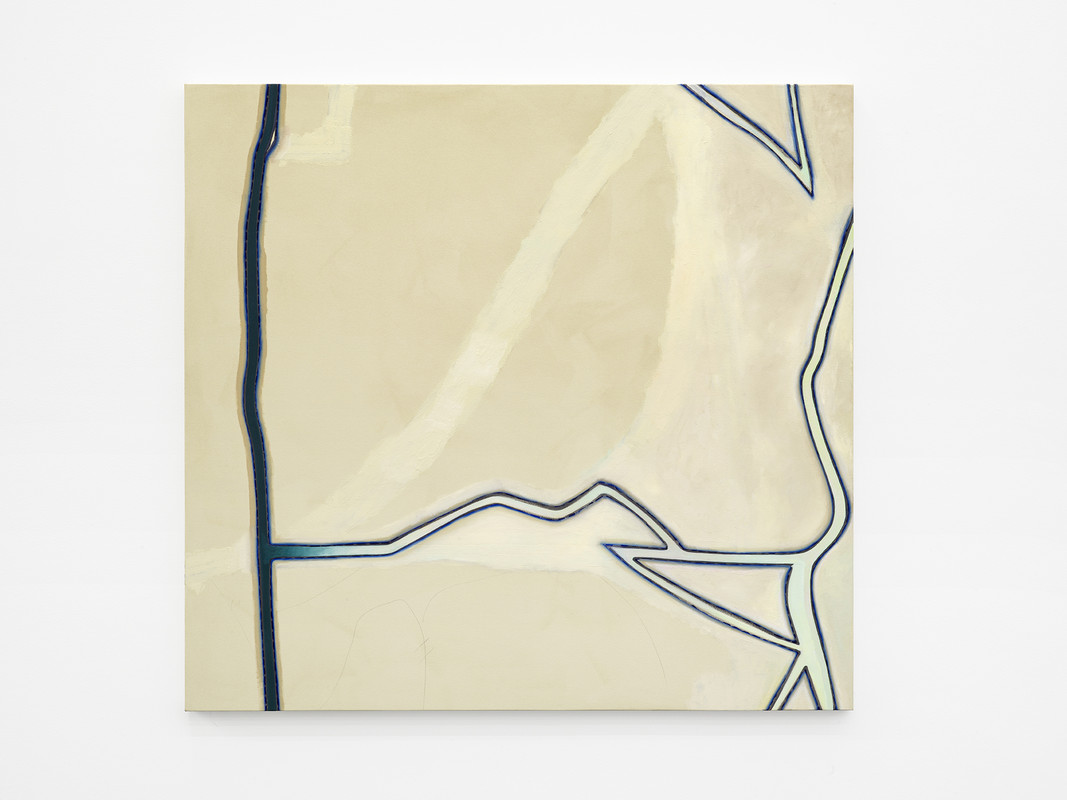

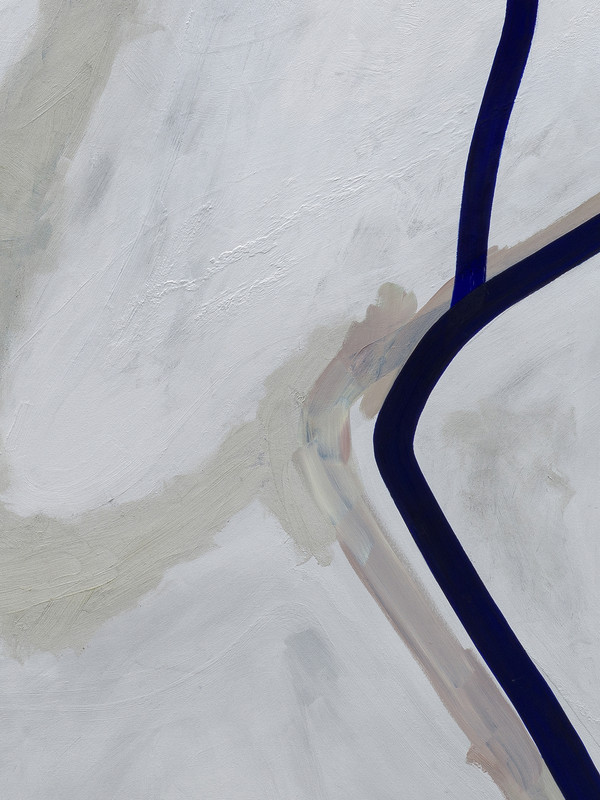

Wade Guyton

September 6 – October 25, 2025

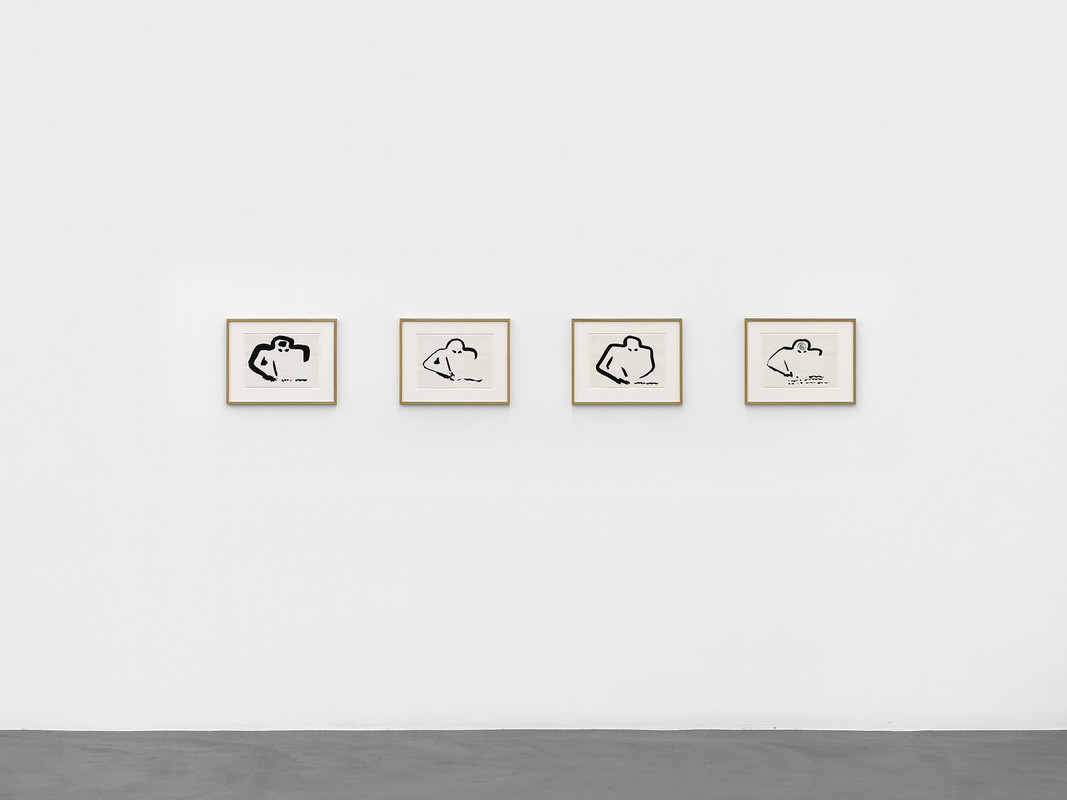

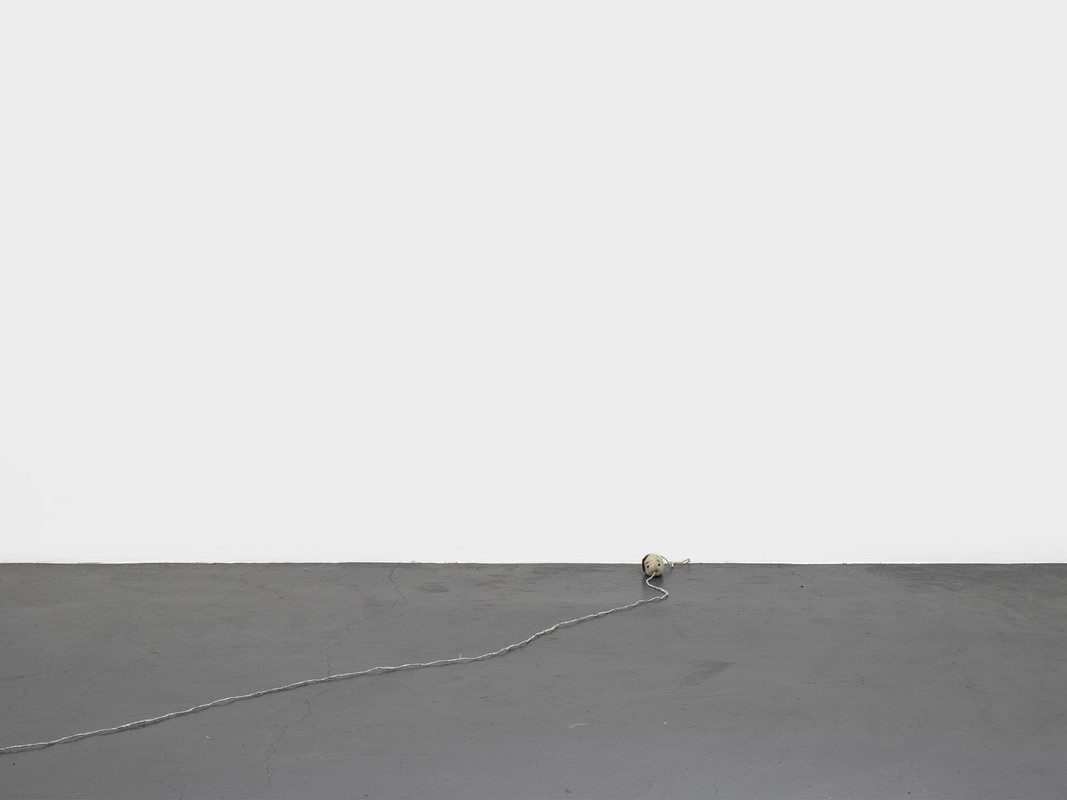

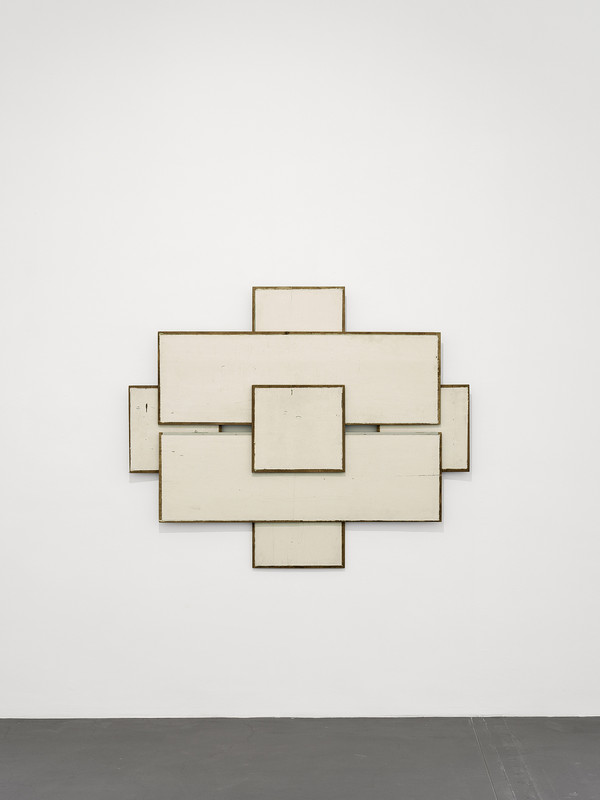

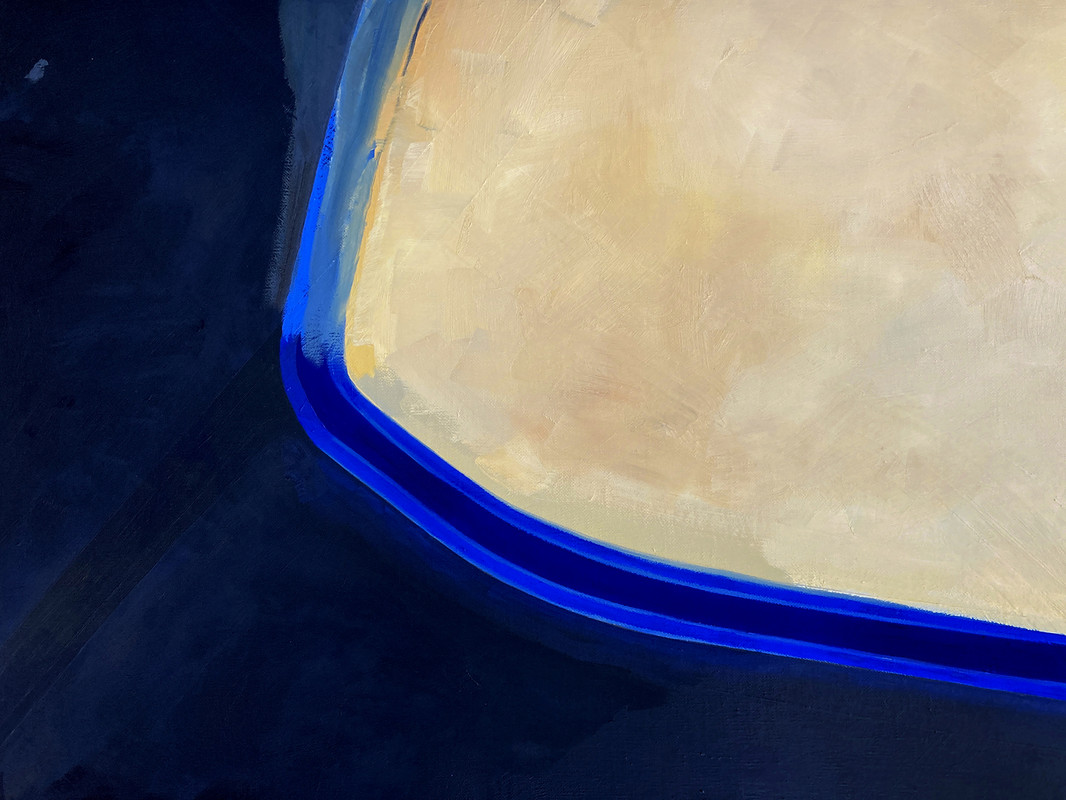

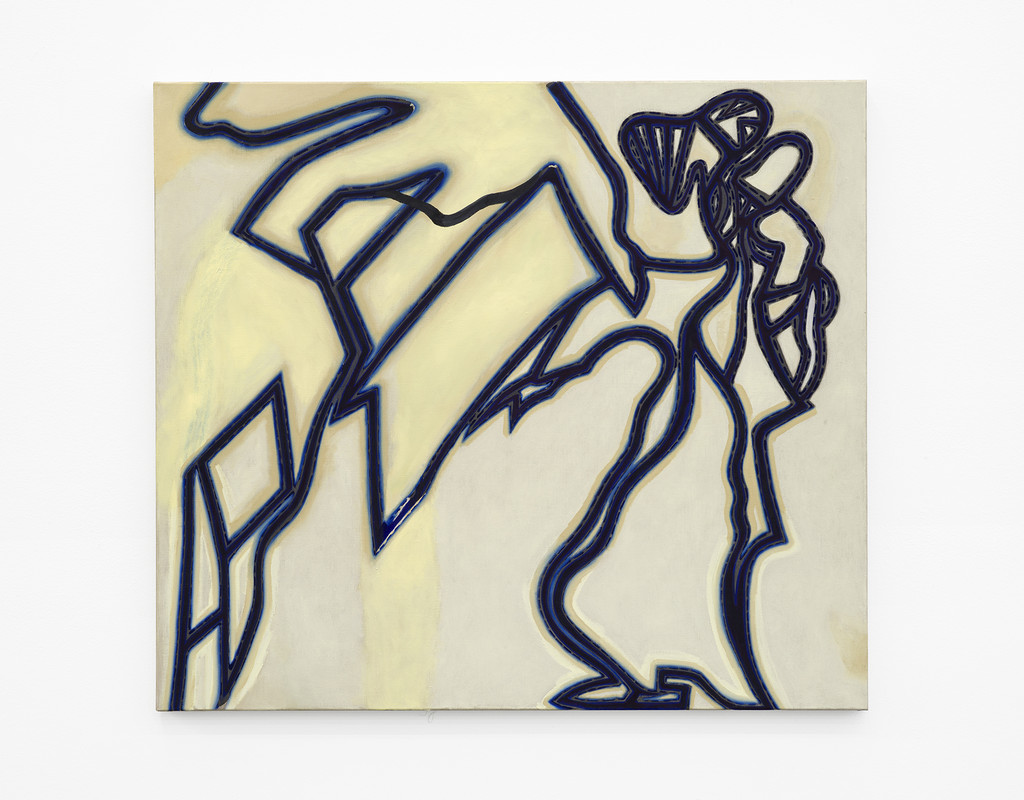

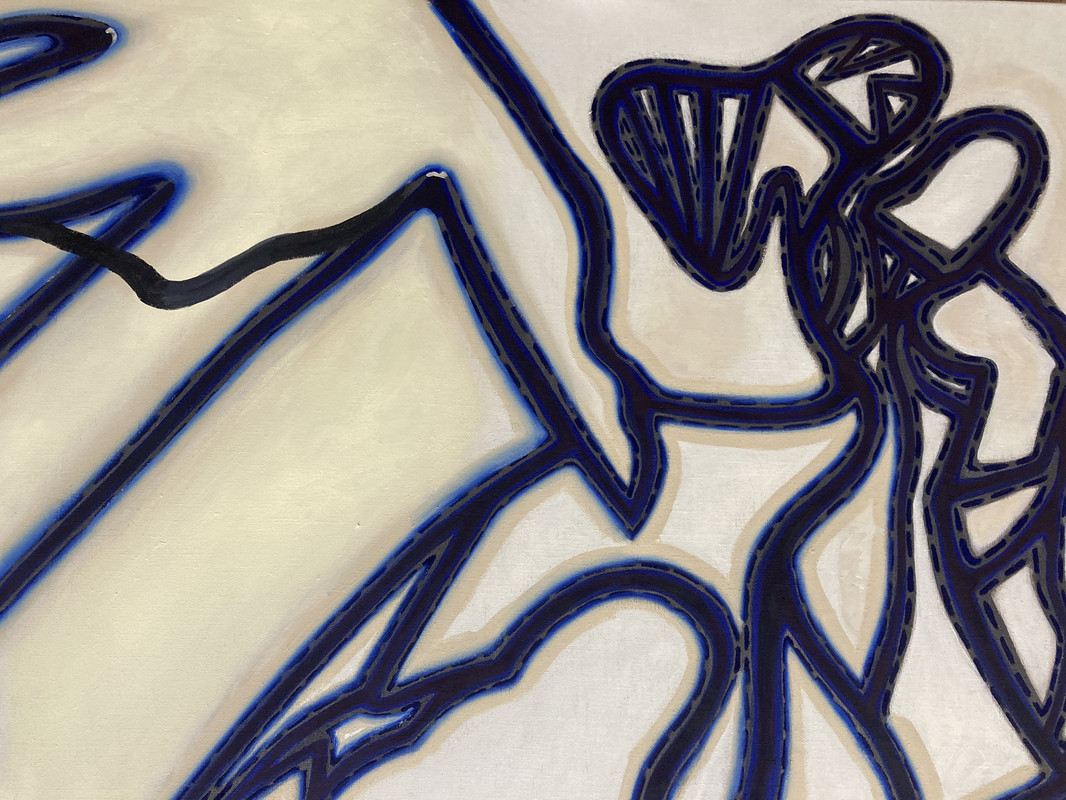

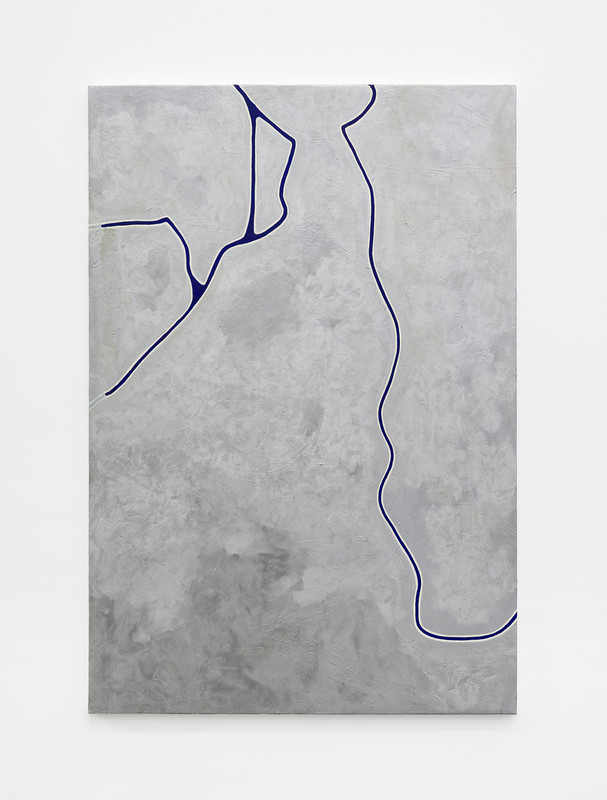

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2024, Cast bronze and aluminum, Ed. 1/2 (+1 AP), 31.9 x 316.9 x 32.1 cm; 35 x 369 x 34 cm

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Wade Guyton, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2024, Cast bronze and aluminum, Ed. 1/2 (+1 AP), 35 x 369 x 34 cm; 31.9 x 316.9 x 32.1 cm

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2025, Epson UltraChrome HDX inkjet on linen, each 91.4 x 68.6 cm ( 36 x 27 inches )

2025

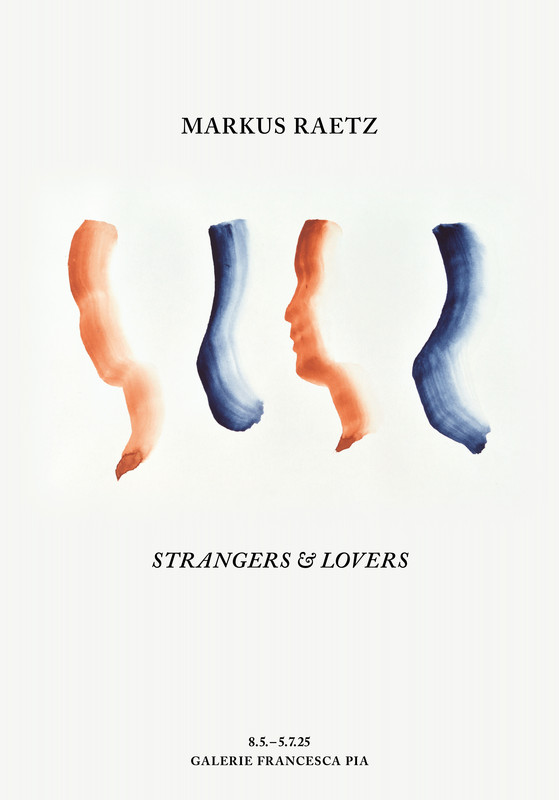

Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers

May 9 – July 5, 2025

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Markus Raetz, Paquet, Bern, 26.3.2008, Cardboard, folded, glued and painted (watercolor); plinth: wood, stained black, waxed, base: cardboard tube, support plate: plywood, 26.1 x 17 x 9 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Philipp Hitz

Markus Raetz, Paquet, Bern, 26.3.2008, Cardboard, folded, glued and painted (watercolor); plinth: wood, stained black, waxed, base: cardboard tube, support plate: plywood, 26.1 x 17 x 9 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Philipp Hitz

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

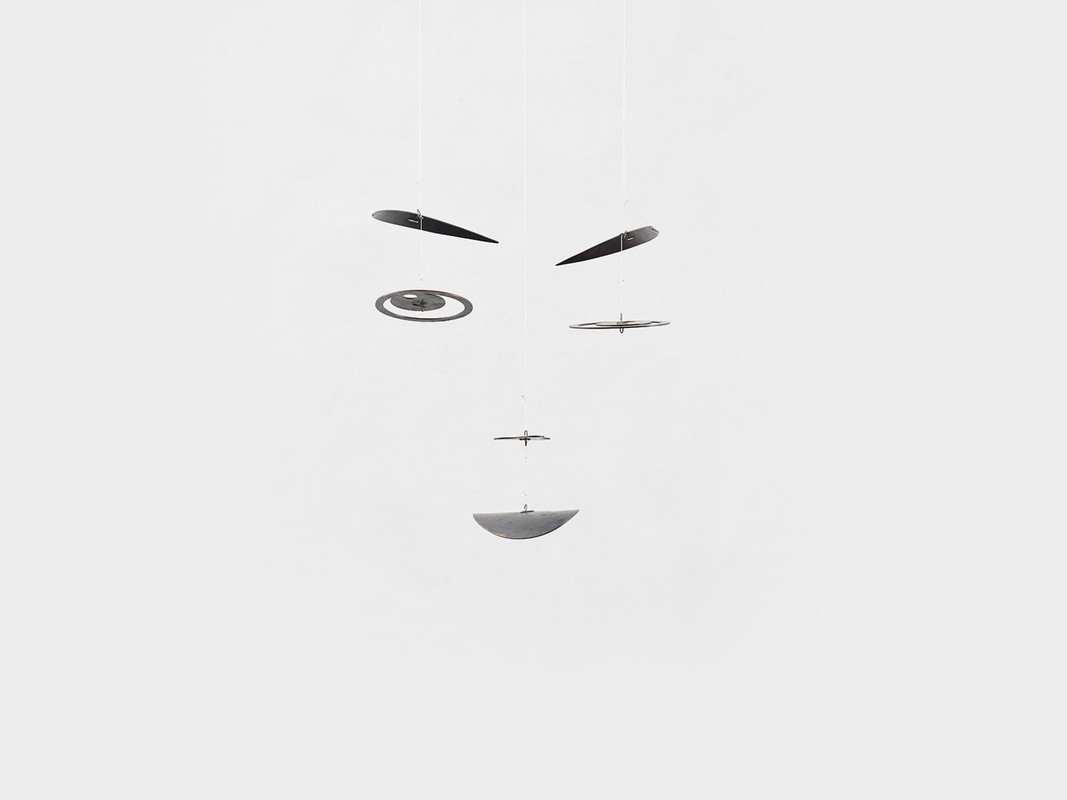

Markus Raetz, Untitled, Bern, 2008–2017, 10 strands, 25 elements: aluminum sheet, raised or folded, suspension: polyamide thread. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

Markus Raetz, Schwarzer Mann (Black Man), Carona/Bern/Mur (Vully-les-Lacs), 1976/1977, Limestone from Saint-Triphon, worked with hammer and chisel, bush hammer, carborundum, Japanese knife, and sandpaper, 33 x 13 x 13 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Philipp Hitz

Markus Raetz, Feldstechermann (Binoculars Man), Lyon, 11.10.1987 / Bern, 2018, Fir wood, carved, plinth: iron, patinated, 46 x 1.8 x 2.1 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

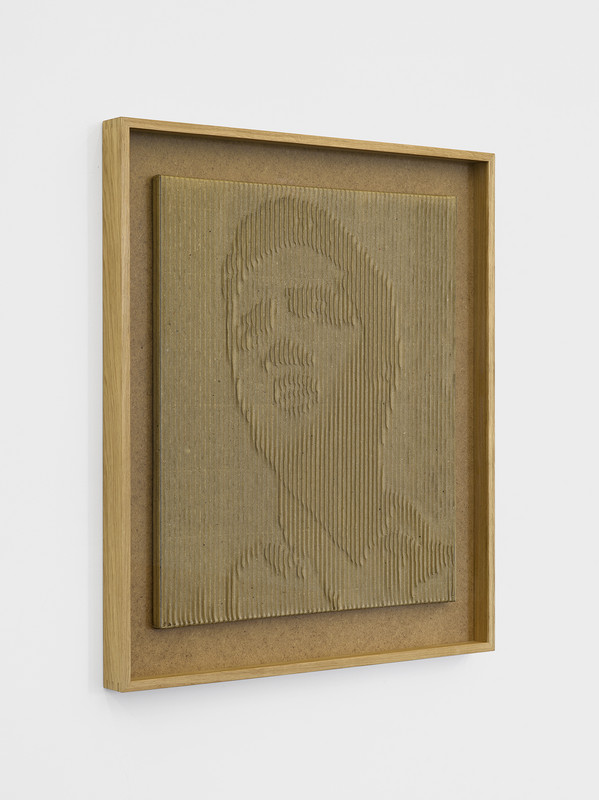

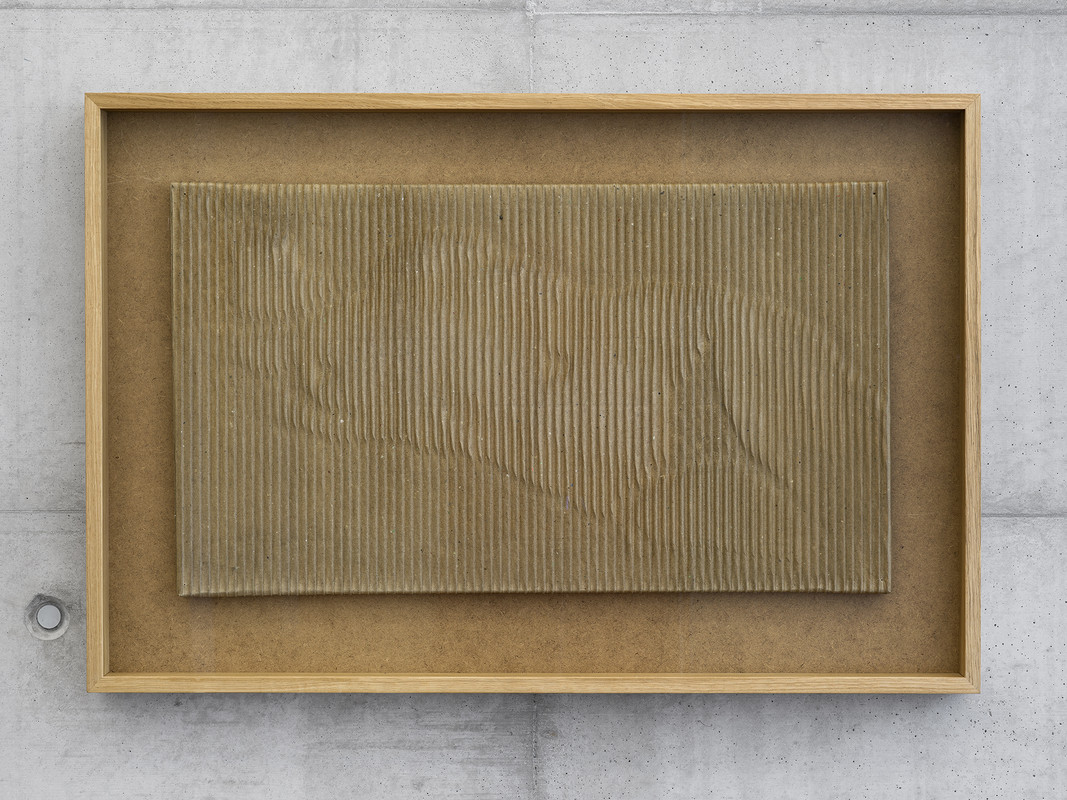

Markus Raetz, Elvis, Bern, Aug. 1978, Corrugated cardboard, shaped and fixed (white glue “Konstruvit”, diluted), 87 x 75 x 6 cm. Photo: Cedric Mussano

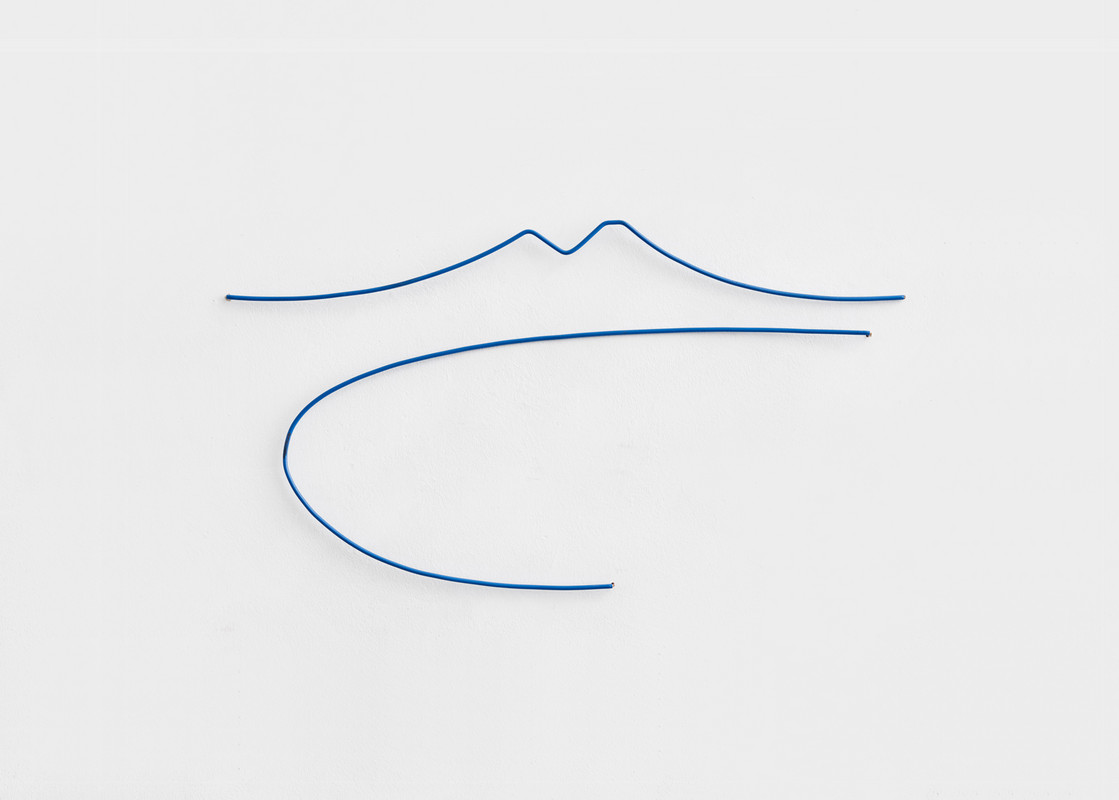

Markus Raetz, Der Golf von Neapel (Gulf of Neaples), 1980, Insulated copper wire, 27 x 50 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Markus Raetz, Form in Space, Bern, 1991/2017, Cast aluminum, rod: aluminum, fluted, with brass collar (found object), plinth: bronze (found object), 43.3 x 28.8 x 12.5 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

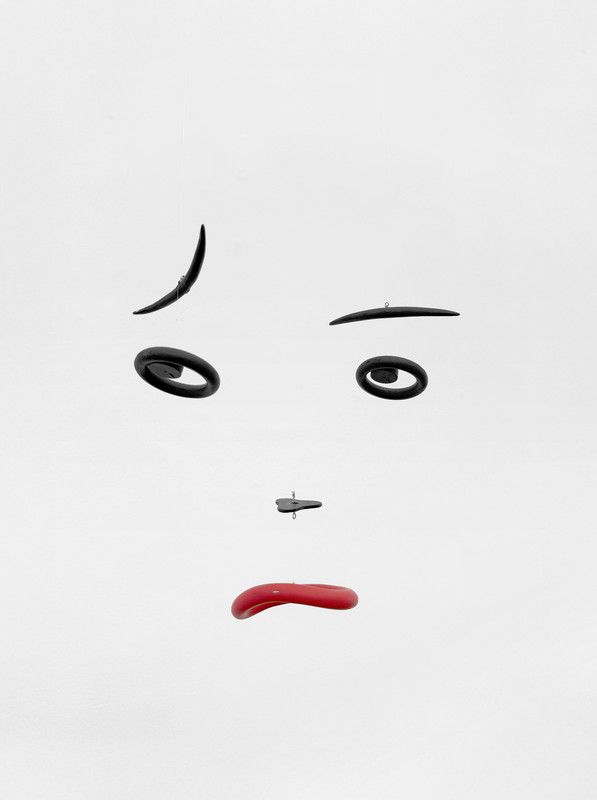

Markus Raetz, Duo, Bern, Aug. 2006 / May 2007, Wood, painted, modeling paste, 3 sails: aluminum sheet, raised, suspension: iron wire, polyamide thread

Markus Raetz, Untitled, Bern, ca. 1996, Bronze sheet, painted, suspension: iron wire, thread. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

Markus Raetz, Tori, Bern, 1968, Screen print on hardboard, Ed. 30, 42 x 53 x 2.2 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA/Zürich Peter Lauri, Bern

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

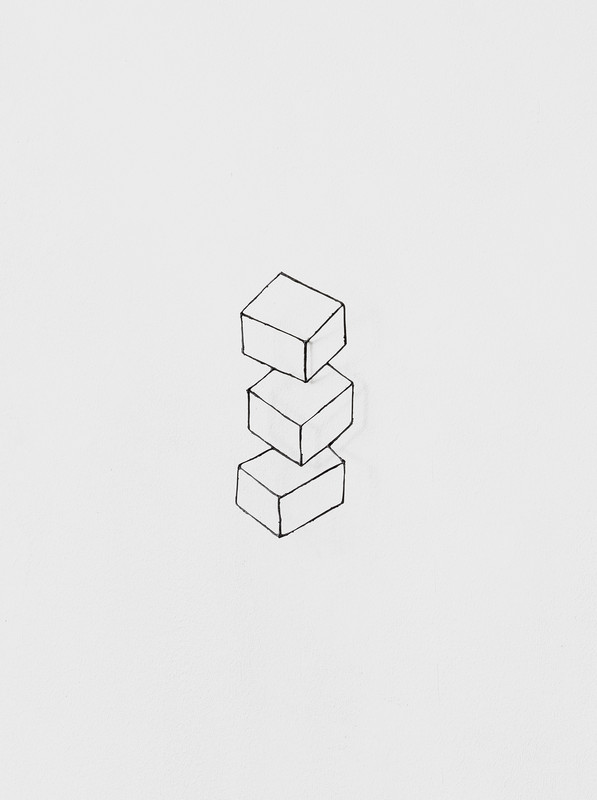

Markus Raetz, Drei Quader (Three cuboids), Bern, 29.7.2008, Galvanized iron wire, soldered and painted (black primer), 26.3 x 14.3 x 3.2 cm. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Markus Raetz, Zwei Zylinder (Two Cylinders), 10.4.2008 / 9.12.2010, Aluminum sheet, raised, plinth: oak wood, 18.2 x 0.1 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

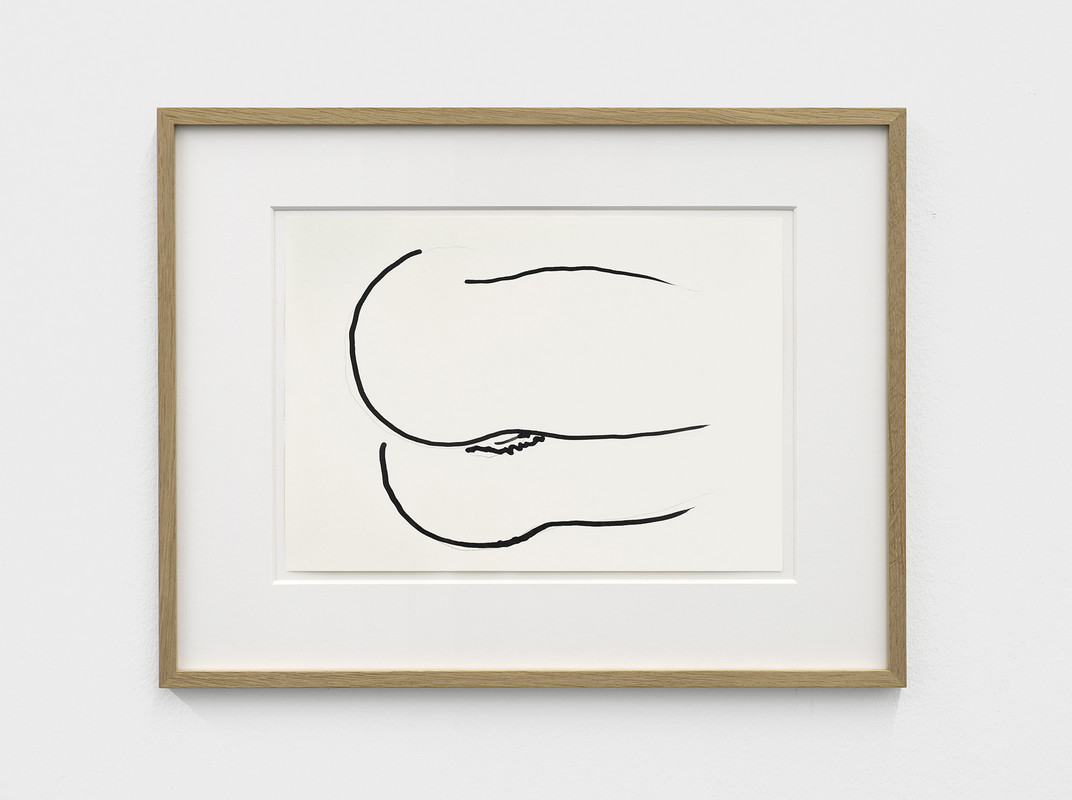

Markus Raetz, Nu, Bern, Aug. 1978, Corrugated cardboard, shaped and fixed (white glue “Konstruvit”, diluted), 87 x 75 x 6 cm. Photo: Cedic Mussano

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

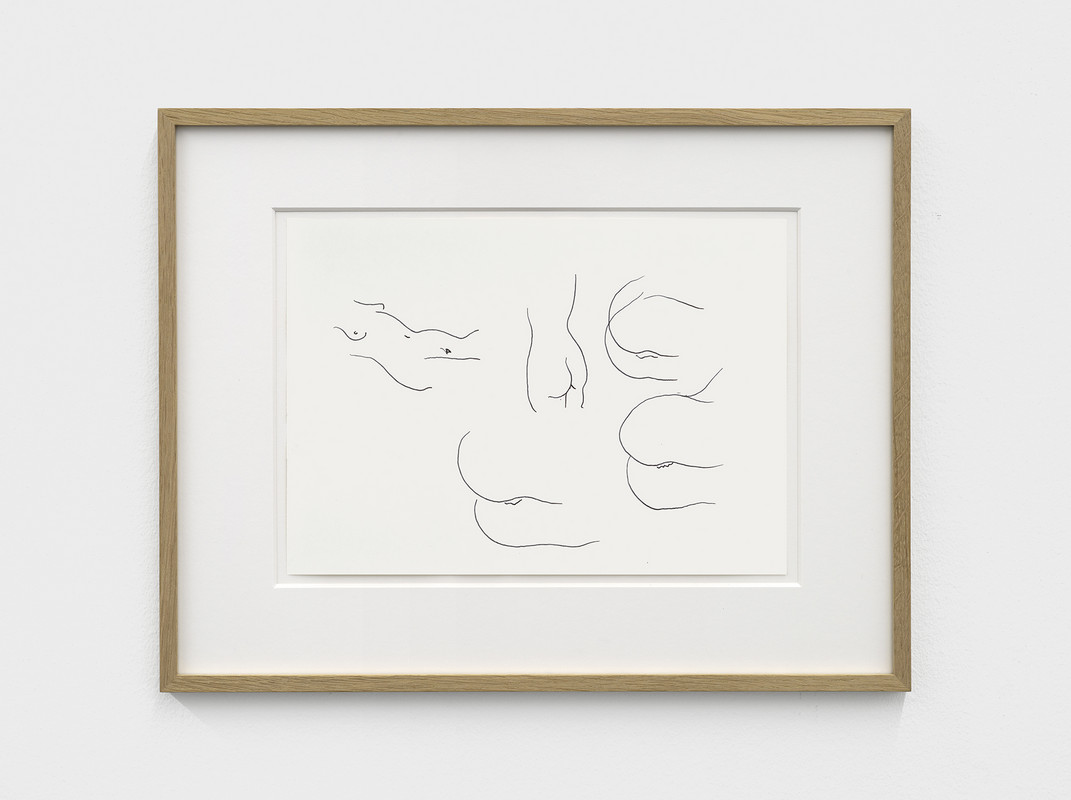

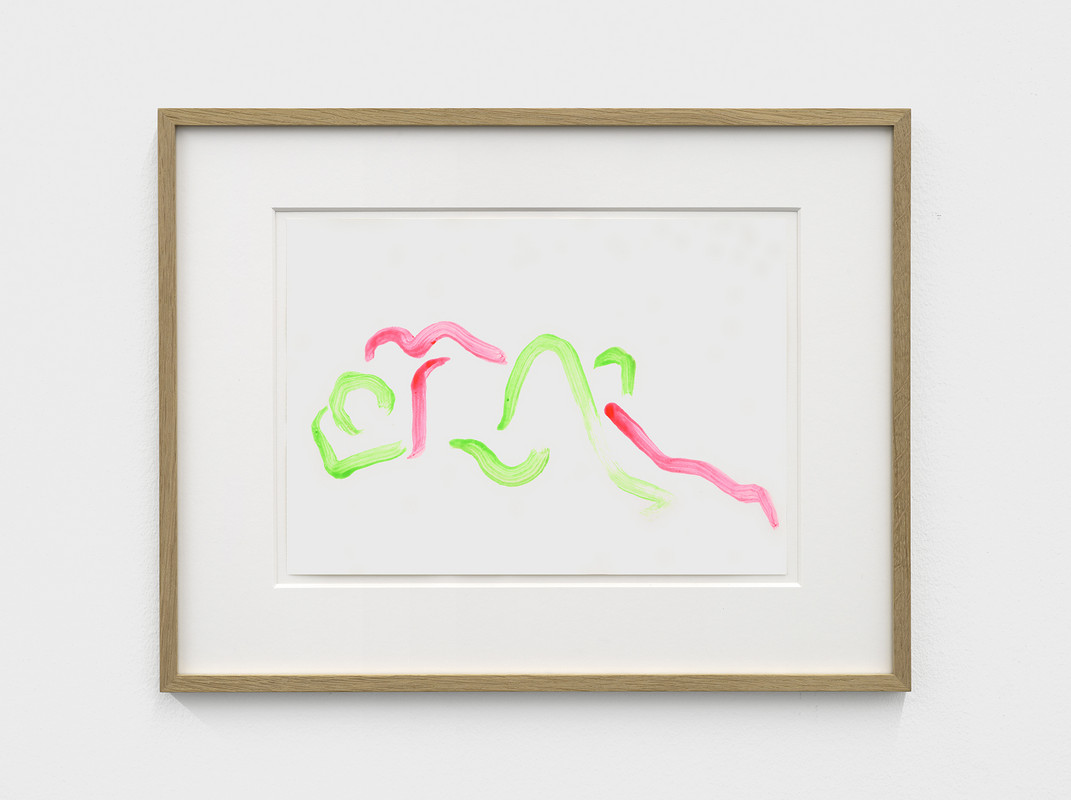

Markus Raetz, Untitled, June / August 1980, Watercolor on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm; Untitled, 19.3.1980, Watercolour on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, March 1980, Watercolor on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Markus Raetz, Nach P. d. F. (After P. d. F.), Bern, Nov. 2002, Aluminum sheets, 16 parts, plywood, painted (acrylic paint), 21.4 x 19.8 x 11.7 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich

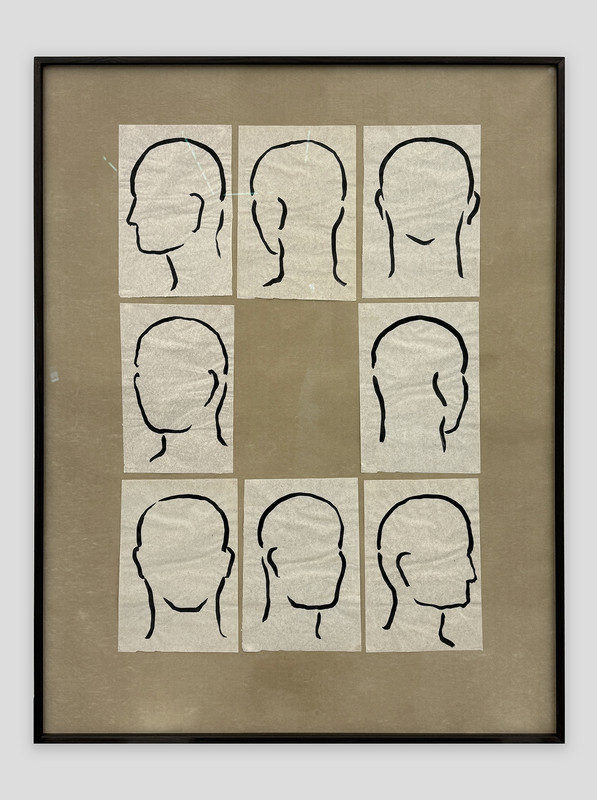

Markus Raetz, Bewogen beweging, 7.9.1983, 8 drawings: ink on tissue paper, mounted on paper, 116.5 x 90.5 x 3 cm

Markus Raetz, Steckkopf Esther, Bern, 1966, Photo paper on cardboard; plinth: pear wood, 28.9 x 20.9 x 20 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

Installation view, Markus Raetz, Strangers & Lovers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

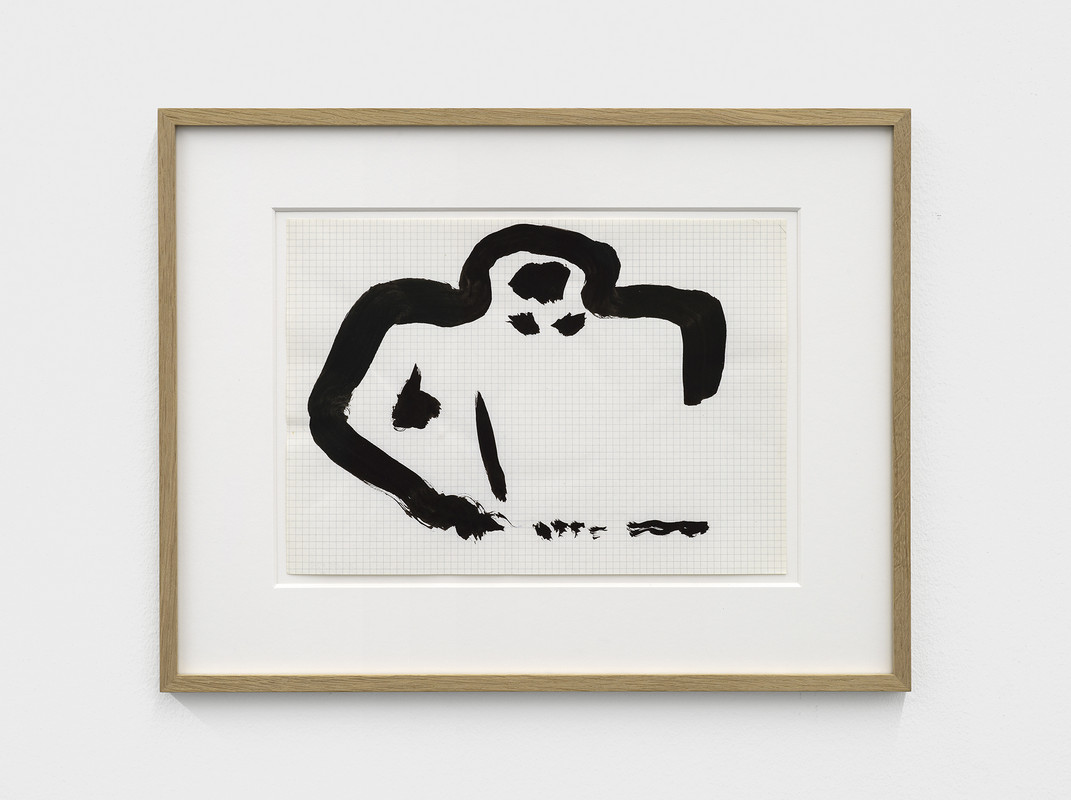

Markus Raetz, Untitled, 28.8.1980, Ink on graph paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Reflexion I–III, 1991, Photogravures with aquatint on paper, Ed. 15/35, each 96.1 x 111.2 x 3.4 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, 18./23.7.1986, Aluminum sheet, raised, 24.2 x 10 x 1.5 cm. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich/Alexander Jaquemet, Erlach

Markus Raetz, Untitled, 1980, Paste paint with luminous pigment on paper, 65.5 x 156.5 x 3 cm

Markus Raetz, Paare (Couples), 1980, Plaster, piped, 6.5 x 19.5 x 1.8 cm; 3.5 x 12 x 1.3 cm

Markus Raetz, Paar (Couple), 1980, Plaster, piped, 13.5 x 32.5 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Akt (Nude), Bern, Aug. 1978, Corrugated cardboard, shaped and fixed (white glue “Konstruvit”, diluted), mounted on stretcher frame, 58 x 87 x 6 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, 12.9.1980, Watercolor and paste paint on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, July / August 1980, Ink on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, July / August 1980, Pencil, dip pen, and ink on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

Markus Raetz, Untitled, April 1980, Paste paint with luminous pigment on paper, 34.3 x 44.3 x 2 cm

2025

Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers

February 8 – April 12, 2025

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Les mains en l’air, 2025, Mixed media, 240 x 160 x 18 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Les mains en l’air (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 240 x 160 x 18 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Les mains en l’air (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 240 x 160 x 18 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, 2025, 2025, Acoustic foam, bells, mirror, metal, 150 x 242 x 12 cm

Sarah Benslimane, 2025 (detail), 2025, Acoustic foam, bells, mirror, metal, 150 x 242 x 12 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, 2025, Mixed media, 280 x 190 x 10 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 280 x 190 x 10 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 280 x 190 x 10 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled, 2025, Mirror, fur dice, 76 x 60 x 15 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled (detail), 2025, Mirror, fur dice, 76 x 60 x 15 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, La panthère des neiges, 2025, Mixed media, 210 x 334 x 7 cm

Sarah Benslimane, La panthère des neiges (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 210 x 334 x 7 cm

Sarah Benslimane, La panthère des neiges (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 210 x 334 x 7 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Rayan, 2025, Acoustic foam, cowskin, plastic, bells, call bell, musical instruments, metal bits, rulers, climbing holds, 185 x 305 x 12 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Rayan (detail), 2025, Acoustic foam, cowskin, plastic, bells, call bell, musical instruments, metal bits, rulers, climbing holds, 185 x 305 x 12 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Rayan (detail), 2025, Acoustic foam, cowskin, plastic, bells, call bell, musical instruments, metal bits, rulers, climbing holds, 185 x 305 x 12 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled, 2025, Mixed media, 180 x 130 x 20 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 180 x 130 x 20 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled (detail), 2025, Mixed media, 180 x 130 x 20 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled, 2025, Mirror, transport etiquette, cork, 60 x 76 x 1 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled (detail), 2025, Mirror, transport etiquette, cork, 60 x 76 x 1 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled, 2025, Mirror, print, tape, 60 x 30 x 9 cm

Sarah Benslimane, Untitled (detail), 2025, Mirror, print, tape, 60 x 30 x 9 cm

Installation view, Sarah Benslimane, Le monde à l’envers, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

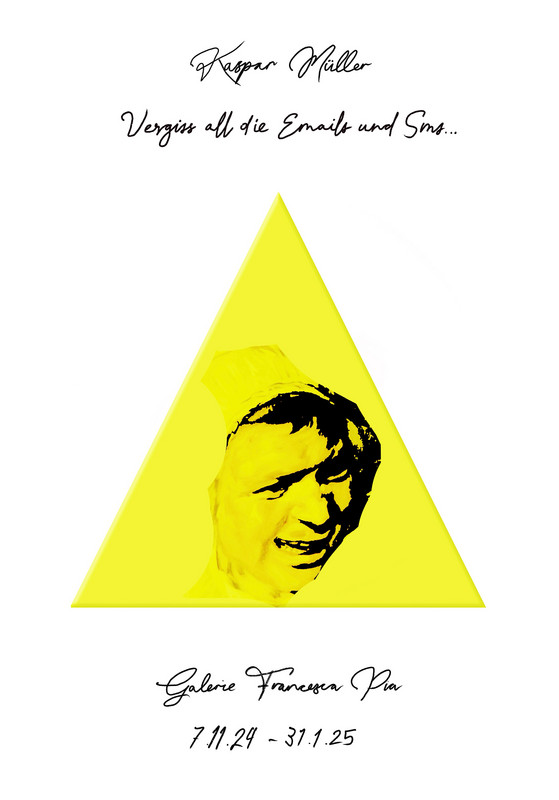

2024

Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…

November 8, 2024 – January 31, 2025

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Adalbert Rogge, Hille Babbe, 1888, 2024, Oil on canvas, 77 x 64 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Semicircle, dark blue, sea breeze, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 65 x 130 x 2 cm

Kaspar Müller, Trapeze, pink, stable, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 95 x 130 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Triangle, orange, rubber/vitamin E, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 54.2 x 31.7 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Rhombus, blue-black, truffle, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 154.3 x 92.8 x 2 cm

Kaspar Müller, Rectangle, burgundy, candy/androstenone, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 35 x 24 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Hexagon, olive green, pipe tobacco, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 82.3 x 47.5 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Parallelogram, purple, grape, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 175 x 70 x 2 cm

Kaspar Müller, Octagon, mint green, panettone/estratetraenol, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 95 x 95 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Circle, orange, frozen pizza, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 95 x 95 x 2 cm

Kaspar Müller, Pentagon, brown, mocha/caffeine, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 90 x 95 x 2 cm

Kaspar Müller, Rectangle, green, savon aux herbes, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 15 x 90.7 x 2 cm

Installation view, Kaspar Müller, Vergiss all die Emails und Sms…, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Kaspar Müller, Square, blue, chamomile/melatonin, 2024, Colored resin panel, scent, 80 x 80 x 2 cm

2024

Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing

August 31 – October 26, 2024

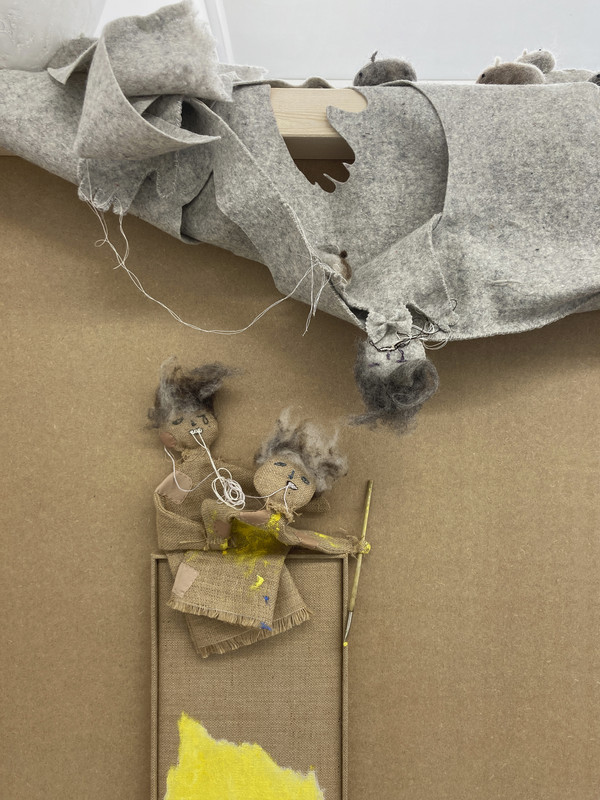

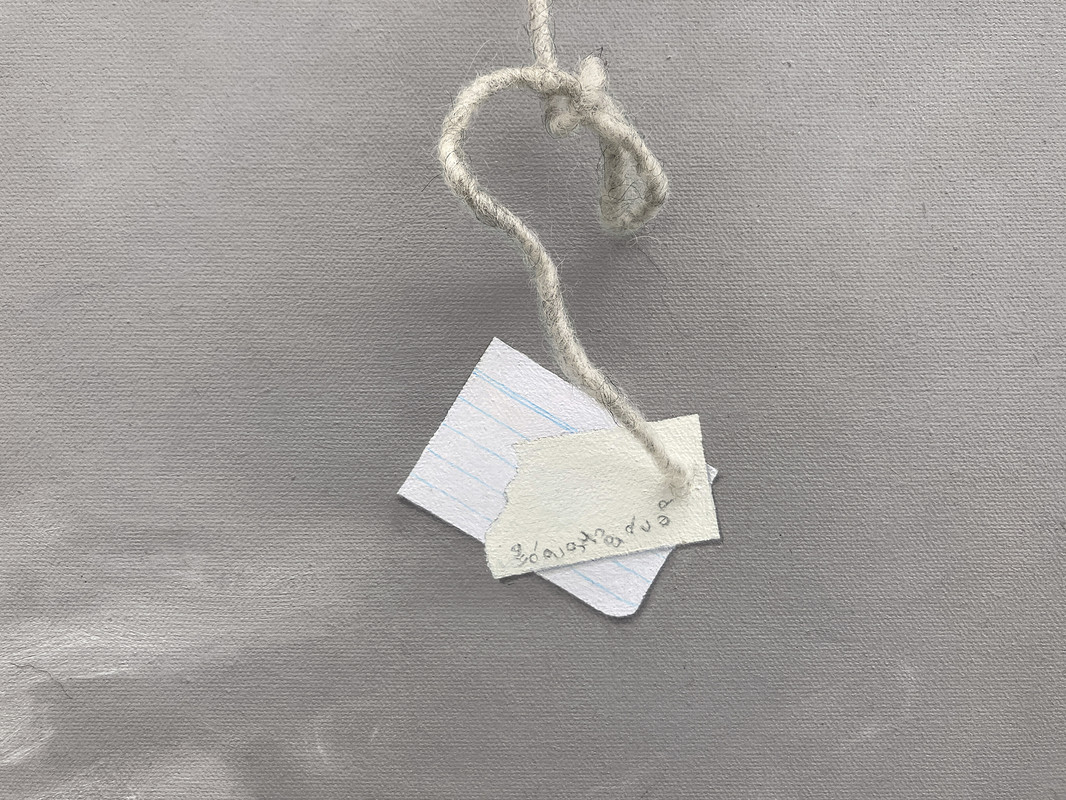

Min Yoon, Digest + ing Time to Emit (detail), 2024, Wool felt, steel, thread, 195 x 100 x 39 cm

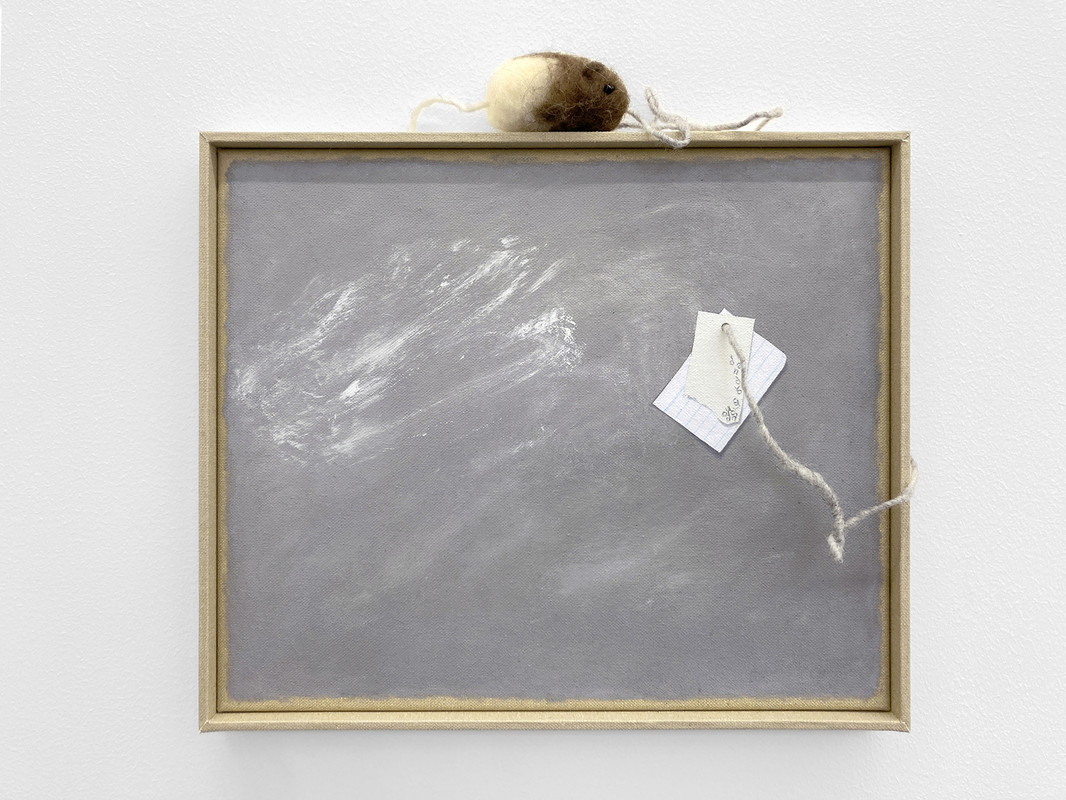

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Digest + ing Time to Emit, 2024, Wool felt, steel, thread, 195 x 100 x 39 cm

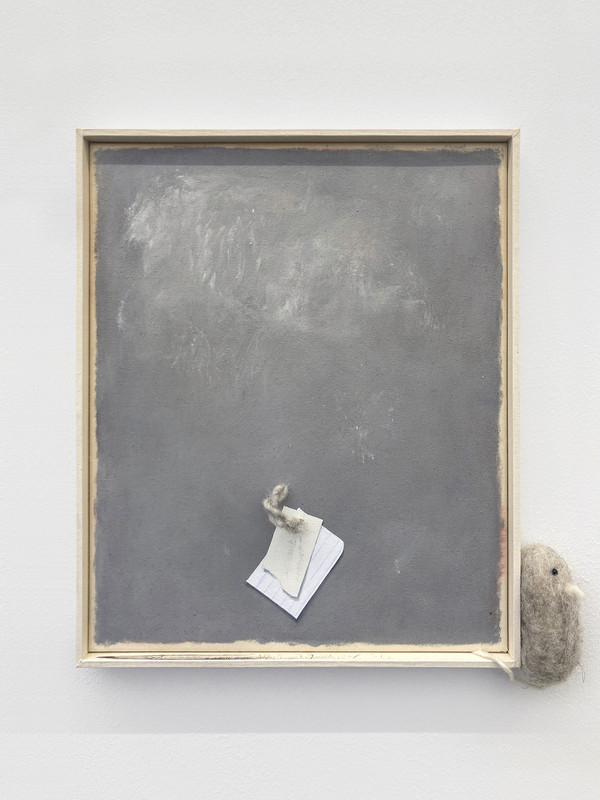

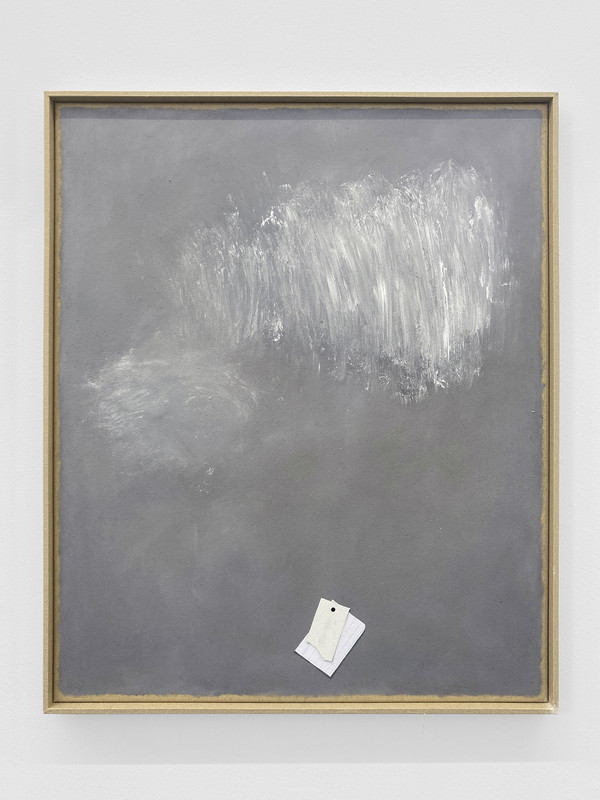

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

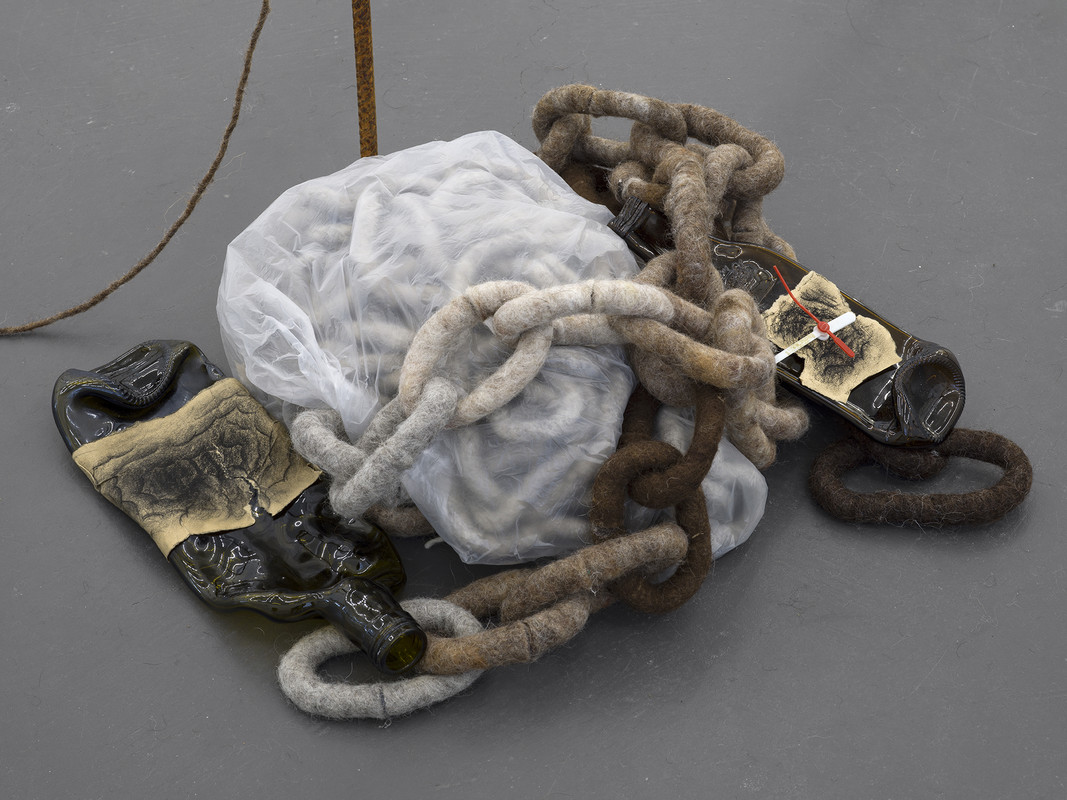

Digest + ing + Wait + ing Time to Emit, 2024, Wool felt, recycled glass bottles, steel, Dimensions variable

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Digest + ing + Wait + ing Time to Emit, 2024, Wool felt, recycled glass bottles, steel, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Digest + ing + Wait + ing Time to Emit (detail), 2024, Wool felt, recycled glass bottles, steel, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Digest + ing + Wait + ing Time to Emit (detail), 2024, Wool felt, recycled glass bottles, steel, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Digest + ing Time to Emit (detail), 2024, Wool felt, steel, thread, 195 x 100 x 39 cm

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Digest + ing + Wait + ing Time to Emit, 2024, Wool felt, recycled glass bottles, steel, Dimensions variable

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Floor + ing Plan B + ing, 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Floor + ing Plan B + ing, 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Floor + ing Plan B + ing (detail), 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Floor + ing Plan B + ing (detail), 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Min Yoon, Floor + ing Plan B + ing (detail), 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Floor + ing Plan B + ing, 2024, Wool felt, thread, recycled glass bottles, Dimensions variable

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Min Yoon, The Creator, 2024, Wool felt, styrofoam, mineral polymer, steel, fabric, polyester filling, approx. 100 x 150 x 45 cm

Min Yoon, The Creator (detail), 2024, Wool felt, styrofoam, mineral polymer, steel, fabric, polyester filling; Break + ing Time (front (proposal)) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 202 x 36.5 x 14 cm

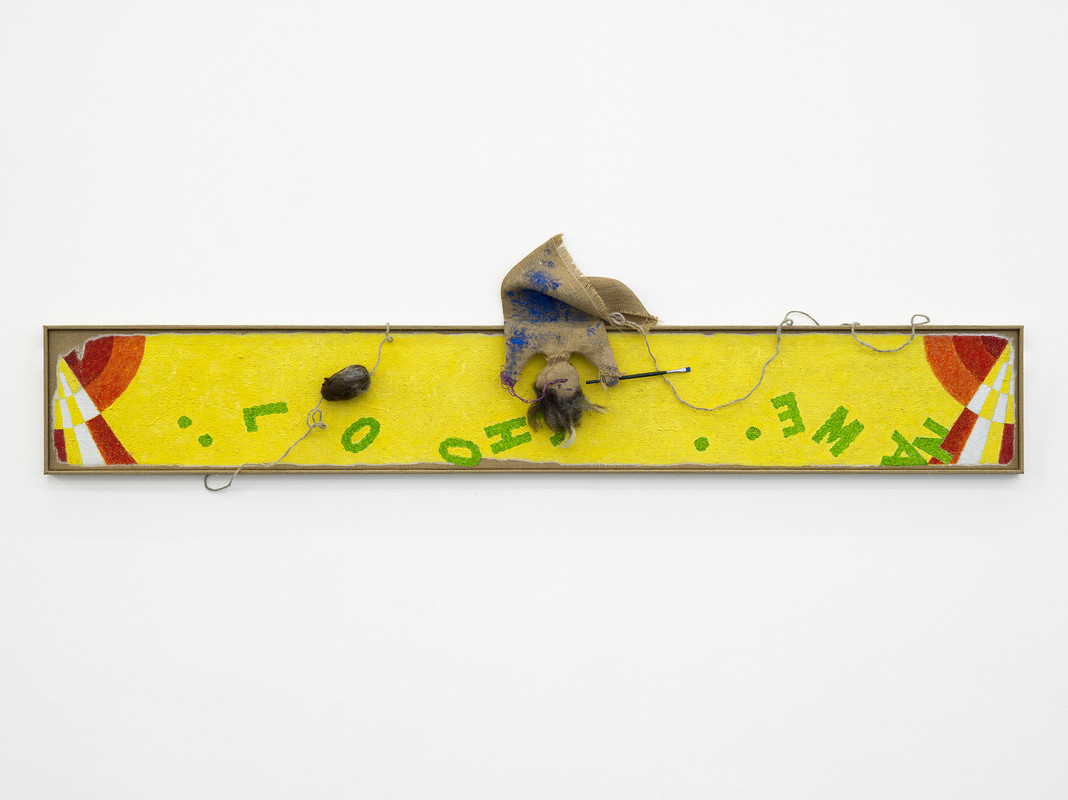

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (front (proposal)), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 202 x 36.5 x 14 cm

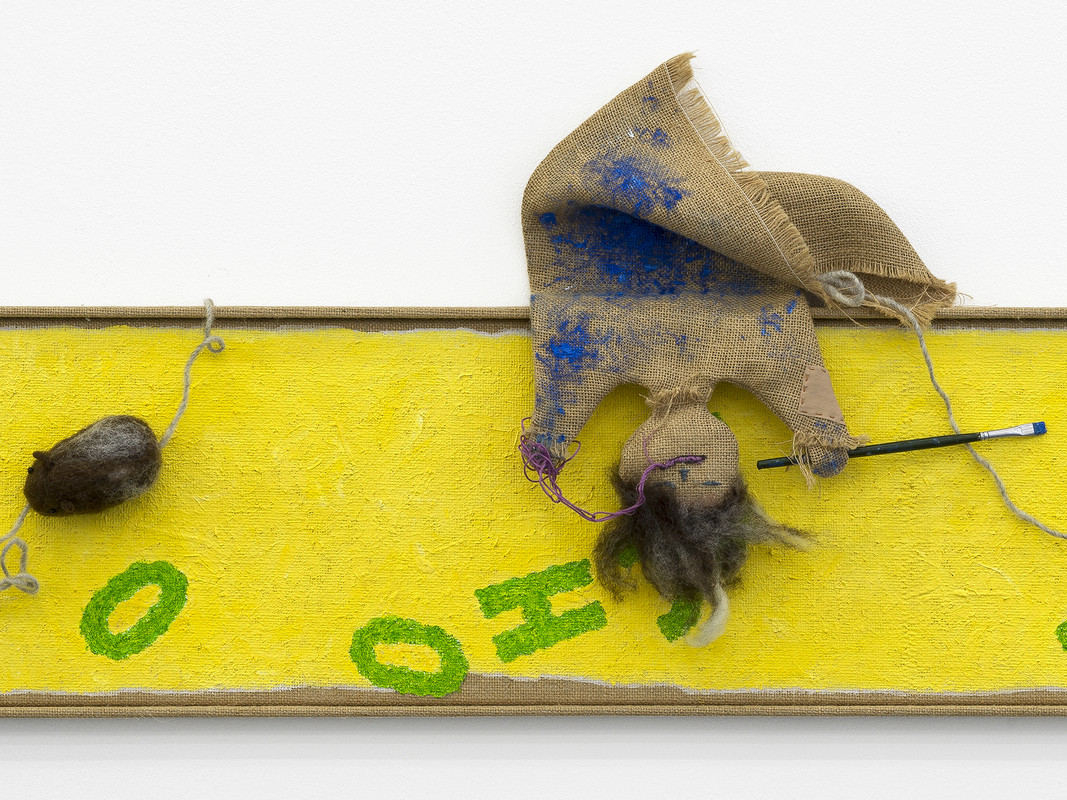

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (front (proposal)) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 202 x 36.5 x 14 cm

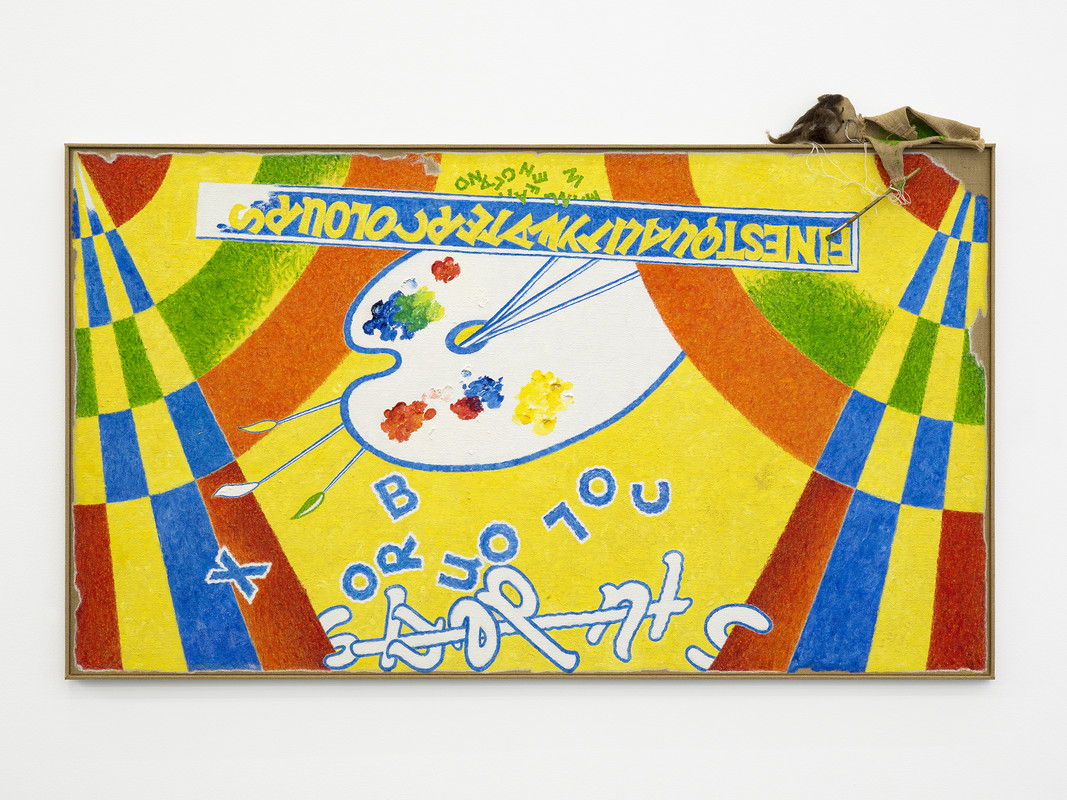

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (top), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 111 x 179.5 x 13 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (top) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 111 x 179.5 x 13 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (left), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 55.5 x 105 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (right), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 127 x 36.5 x 8 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (right) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, brush, artist’s frame, 127 x 36.5 x 8 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (back (proposal)), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, 5 cent coin, brush, artist’s frame, 52 x 177 x 12 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (back (proposal)) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, 5 cent coin, brush, artist’s frame, 52 x 177 x 12 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (bottom), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, 5 cent coin, brush, artist’s frame, 186 x 105.5 x 9 cm

Min Yoon, Break + ing Time (bottom) (detail), 2024, Watermixable oil on burlap, thread, polyester, wool felt, wire, hotpatch, magnets, 5 cent coin, brush, artist’s frame, 186 x 105.5 x 9 cm

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Letter + ing, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, palette, charcoal on paper, feather; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 250 x 70 x 8.5 cm;51.5 x 61.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Letter + ing (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, palette, charcoal on paper, feather; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 250 x 70 x 8.5 cm;51.5 x 61.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Letter + ing (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, palette, charcoal on paper, feather; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 250 x 70 x 8.5 cm; 51.5 x 61.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Dewrong Body, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt, wire; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 185 x 50 x 7.5 cm; 31.5 x 37.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Dewrong Body (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt, wire; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 185 x 50 x 7.5 cm;31.5 x 37.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Dewrong Body (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt, wire; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 185 x 50 x 7.5 cm;31.5 x 37.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Lilac Position, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt; Oil on canvas, wool felt, artist’s frame, 137 x 38 x 7.5 cm; 16 x 19 x 2.5 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Lilac Position (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt; Oil on canvas, wool felt, artist’s frame, 137 x 38 x 7.5 cm;16 x 19 x 2.5 cm

Min Yoon, A, G + ing: Inwrong Body, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles; Oil on canvas, artist’s frame, 102 x 28 x 6.5 cm; 8 x 9.5 x 2 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing + ing, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt, thread, fabric; Oil on canvas, artist’s frame, 60 x 58 x 7 cm; 19 x 16 x 2.5 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing + ing (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, wool felt, thread, fabric; Oil on canvas, artist’s frame, 60 x 58 x 7 cm; 19 x 16 x 2.5 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing: 00:60 ot 00:81, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, pencil on paper, set squares; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 92 x 85 x 8 cm; 37.5 x 31.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing: 00:60 ot 00:81 (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, pencil on paper, set squares; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 92 x 85 x 8 cm; 37.5 x 31.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing: 00:60 ot 00:81 (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, pencil on paper, set squares; Oil on canvas, wool felt, thread, artist’s frame, 92 x 85 x 8 cm; 37.5 x 31.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing: Nah + Da + Um - False Friend, 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, fabric, tubes of oil paint; Oil on canvas, artist’s frame, 154 x 150 x 9 cm; 61.5 x 51.5 x 3 cm

Min Yoon, B + ing: Nah + Da + Um - False Friend (detail), 2024, 2 parts: Plywood, wooden handles, fabric, tubes of oil paint; Oil on canvas, artist’s frame, 154 x 150 x 9 cm; 61.5 x 51.5 x 3 cm

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Min Yoon, Exit Snail Enter Snail, 2024, Wool felt, cardboard, thread, wire, approx. 60 x 100 x 70 cm

Min Yoon, The Creator, 2024, Wool felt, styrofoam, mineral polymer, steel, fabric, polyester filling, approx. 100 x 150 x 45 cm

Installation view, Min Yoon, Perspectives + ing, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

2024

Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie

Marie Angeletti, Lutz Bacher, Olga Balema, Beverly Buchanan, Isabelle Cornaro, Rochelle Feinstein, Pati Hill, Steffani Jemison, Ana Jotta, Sherrie Levine, Katja Mater, Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Hana Miletić, Cinzia Ruggeri, Sturtevant, Eleanor Ivory Weber & Camilla Wills (Divided Publishing)

June 8 – August 23, 2024

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

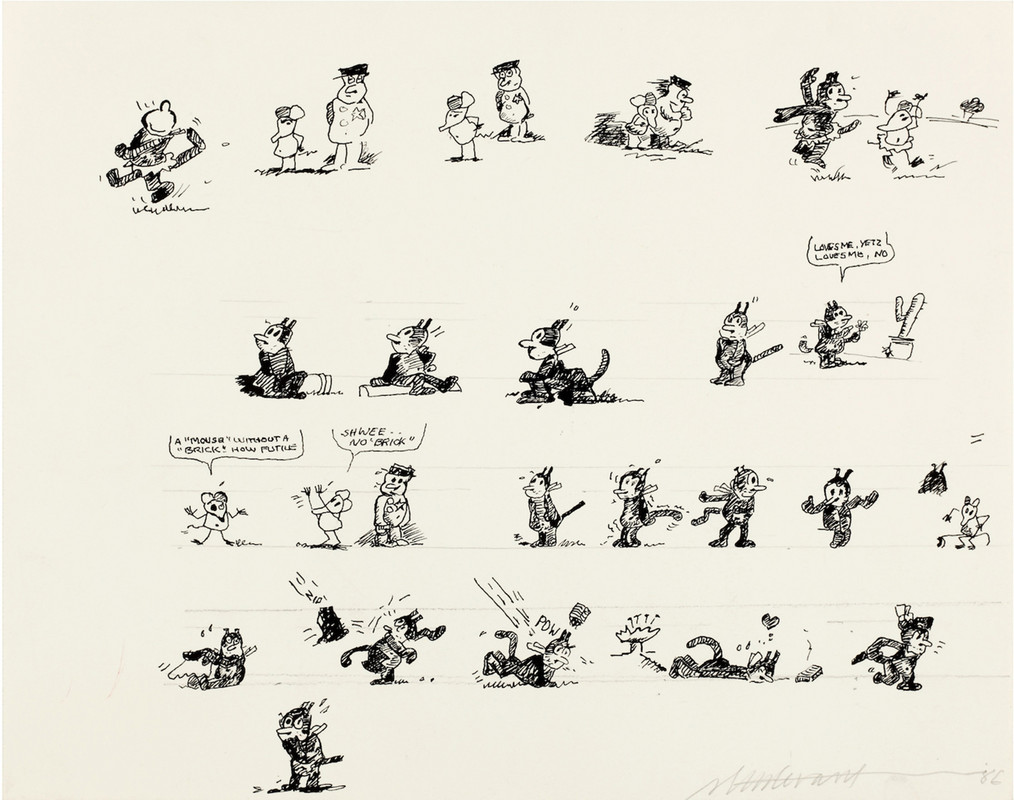

Sturtevant, Krazy Kat, 1983, Ink and graphite pencil on paper, passe-partout, frame, 20.7 × 24.6 cm; 28 × 35.4 cm (framed)

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Naoïse, 2002, Digitized mini DV, color, no sound, 7:30 min

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

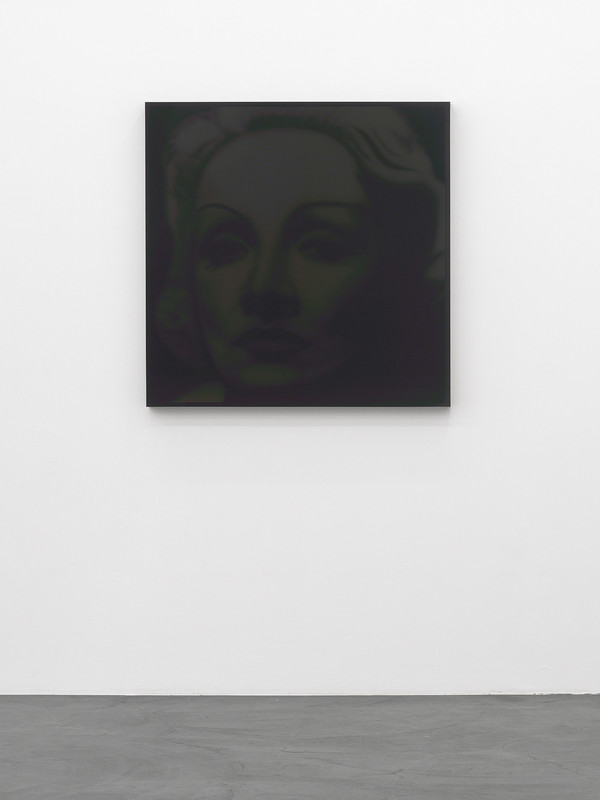

Lutz Bacher, Marlene, 2018, Acrylic on canvas, framed in black plexiglass, 122 x 122 x 7.5 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Steffani Jemison, Same Time, 2017, Acrylic on clear polyester film, 119.4 x 50.8 cm

Steffani Jemison, Same Time, 2017, Acrylic on clear polyester film, 76.2 x 50.8 cm

Steffani Jemison, Untitled, 2021, Acrylic, tempered glass table top, hardware, 149.9 x 76.2 x 12.7 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

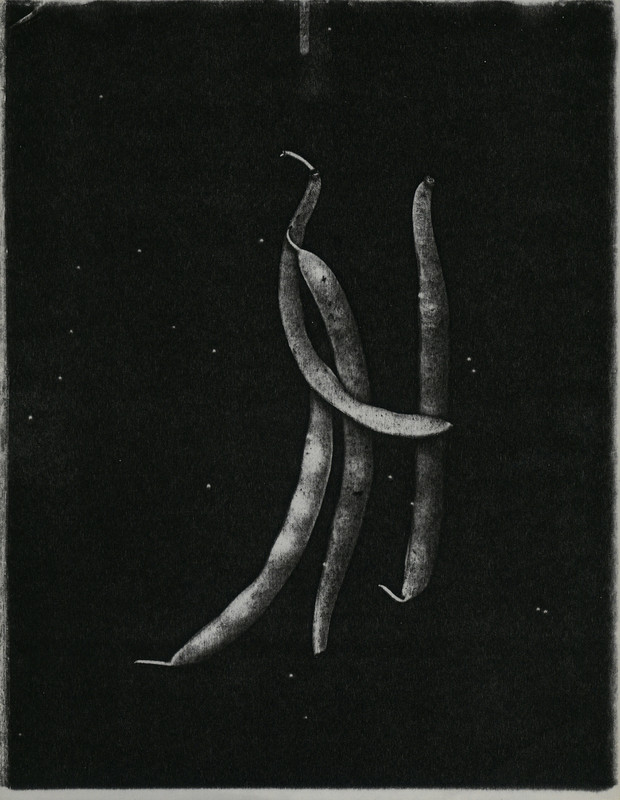

Pati Hill, Untitled (beans), c. 1975–79, Xerograph, 28 × 21.5 cm

Pati Hill, Untitled (feather), 1979, Xerograph, annotated, signed and dated 1979 on verso, 21.6 × 35.3 cm

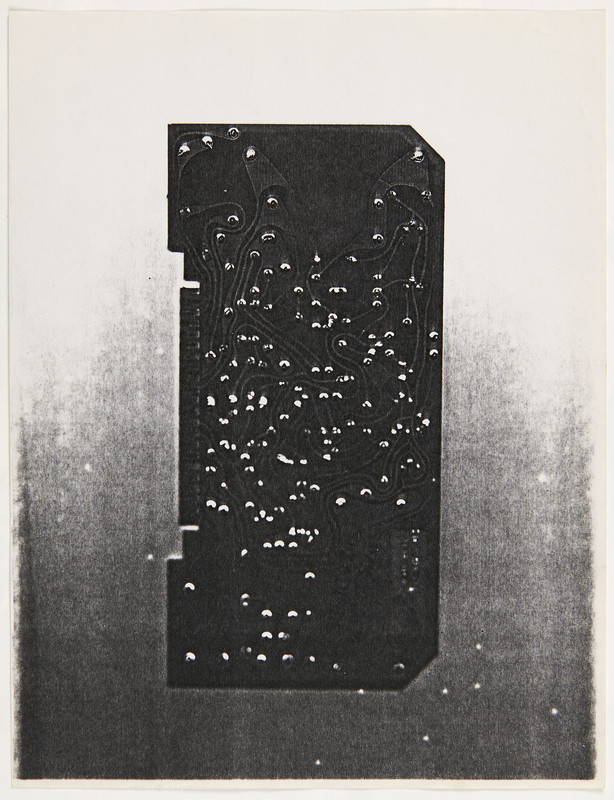

Pati Hill, Untitled (circuit), c. 1977–79, Xerograph, signed on the back, 28.9 × 21.6 cm

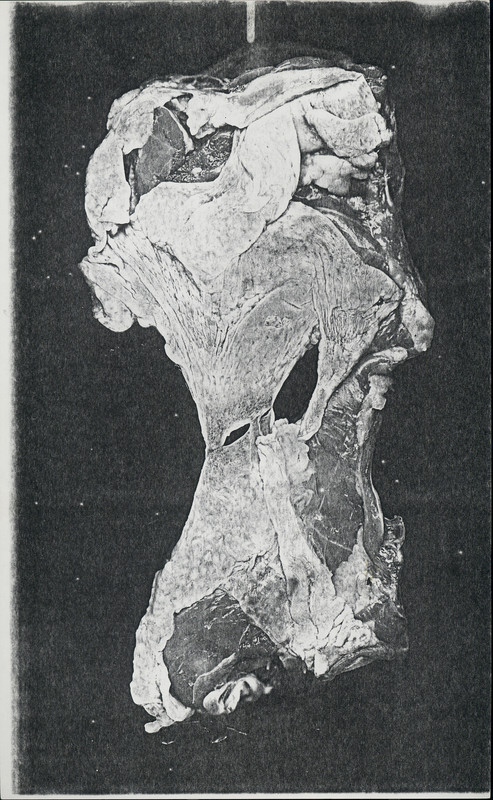

Pati Hill, Untitled (meat), c. 1977–79, Xerograph, 35.5 × 21 cm

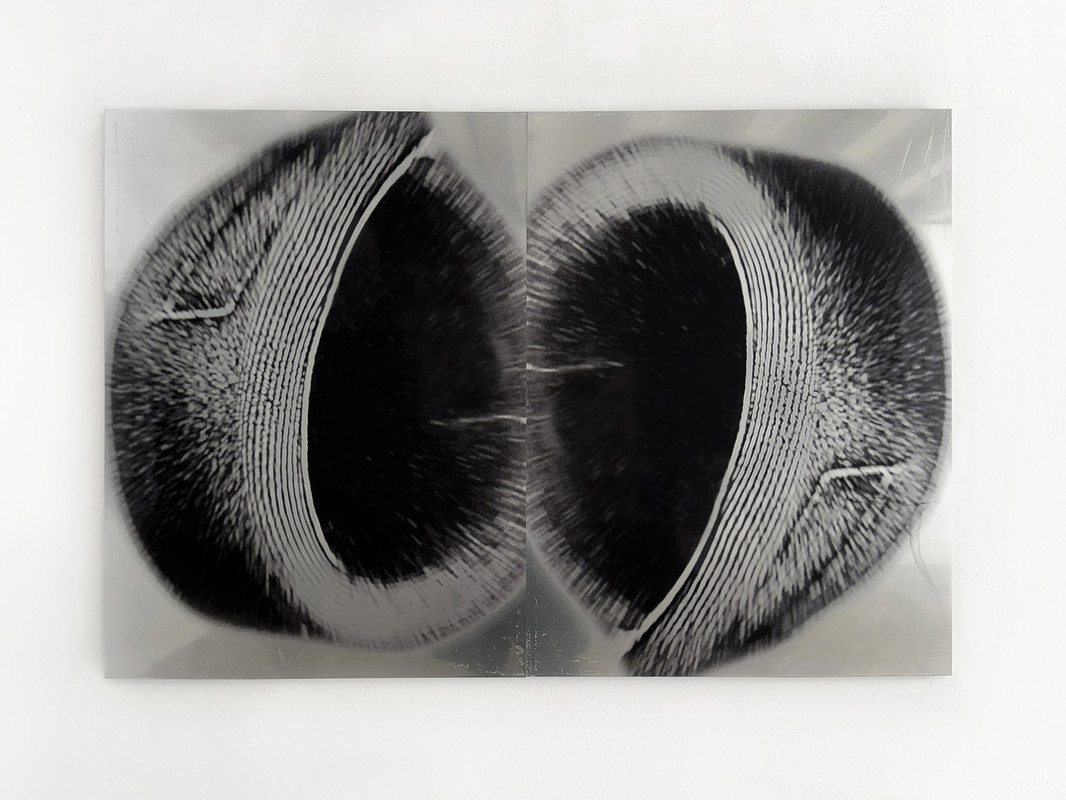

Pati Hill, Untitled, c. 1980, Xerograph, 21 × 32.9 cm

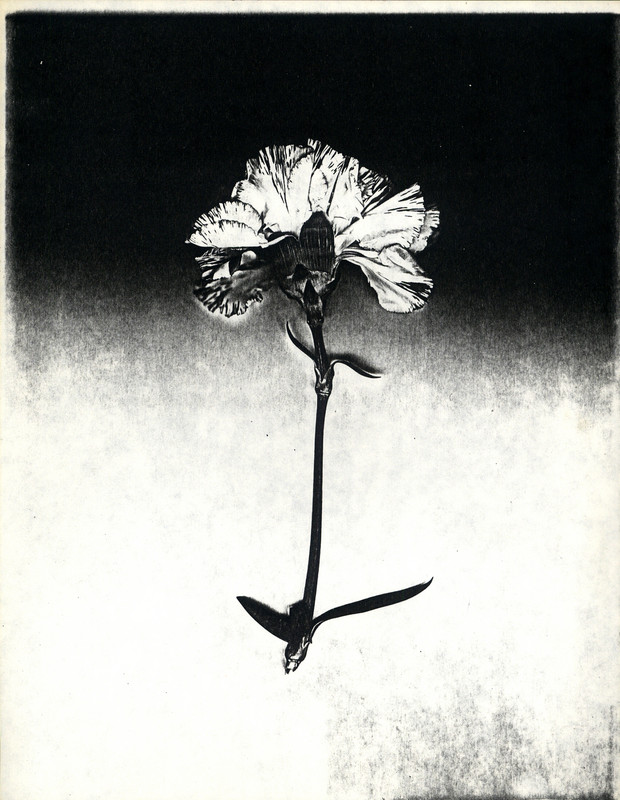

Pati Hill, Untitled (carnation), c. 1977–79, Xerograph, 28 × 21.5 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Olga Balema, Loop 56210, 2023, Polycarbonate sheeting, acrylic paint, solvent, 62.9 x 24.1 x 83.8 cm

Marie Angeletti, Minerve, 2023, Digital print on painted dibond, two parts, each 110 x 82.5 cm

Olga Balema, Loop 12286, 2023, Polycarbonate sheeting, acrylic paint, solvent, 34.3 x 41.9 x 160 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Marie Angeletti, Untitled, 2023, Digital print on painted dibond, 110 x 85 cm

Beverly Buchanan, Untitled, c. 1971–1988, Iron, 15.2 x 14 x 33 cm

Beverly Buchanan, Untitled (Miniature Architectural Construction), c. 1983, Cast concrete and enamel paint, 7.6 x 7 x 6.4 cm

Beverly Buchanan, Untitled, c. 1980, Oyster shell tabby mixture, 25.4 x 11.4 x 6.4 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Matthis, 2002, Digitized mini DV, color, no sound, 1:06 min

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Sherrie Levine, Coyote Postcard Collage: 1–16, 1999, 16 individual postcards, framed, each 52.5 x 42 x 2.5 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

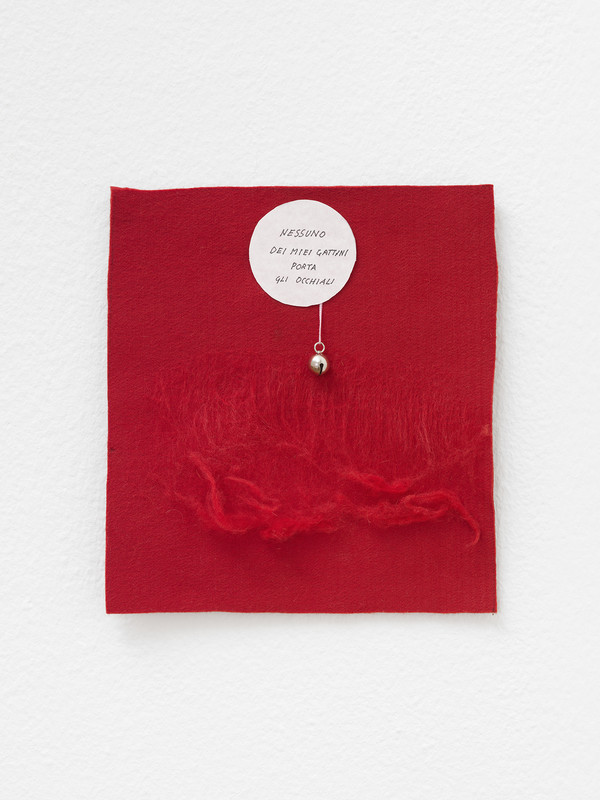

Cinzia Ruggeri, Nessuno dei miei gattini porta gli occhiali, 2018, Felt, collage and cat bell , 25 x 22 cm

Marie Angeletti, Canoe, 2024, 110 x 50 x 70 cm

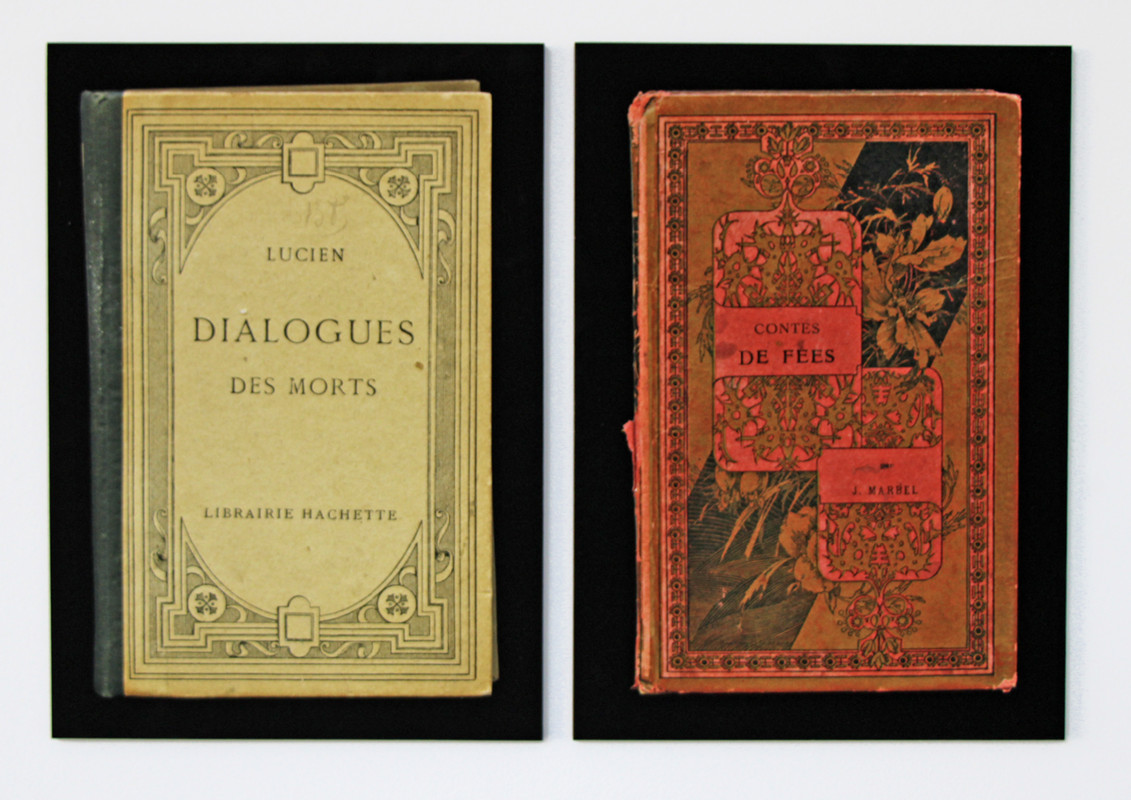

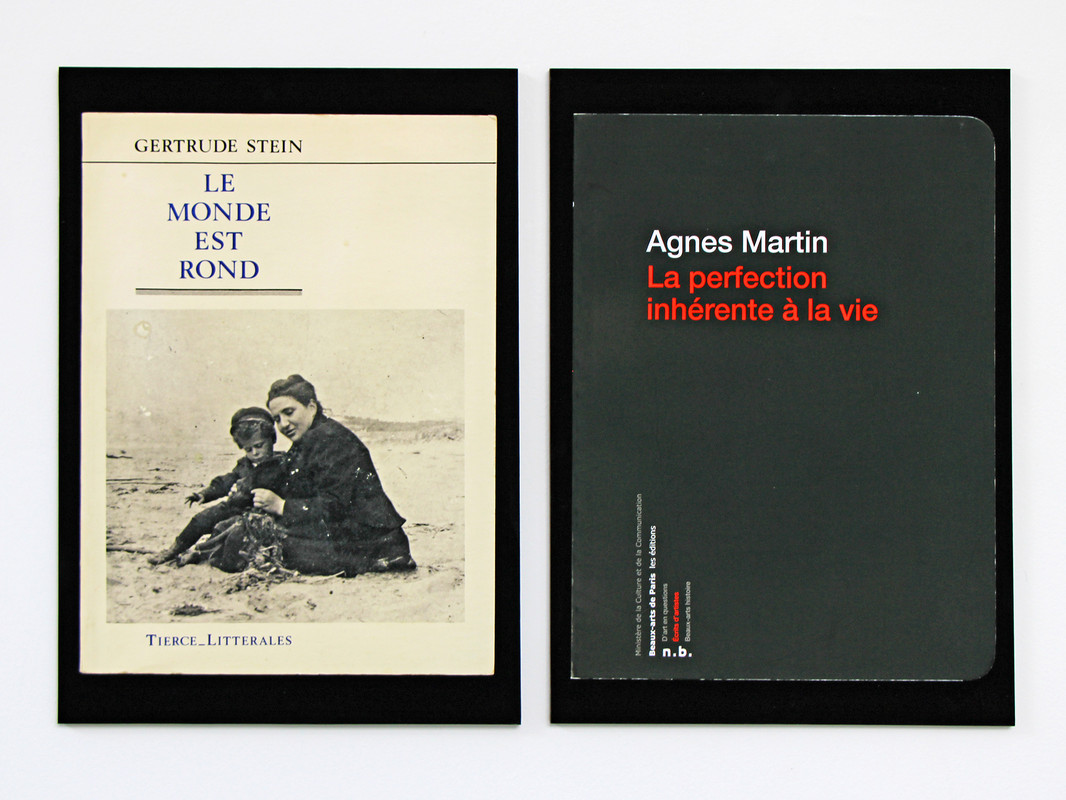

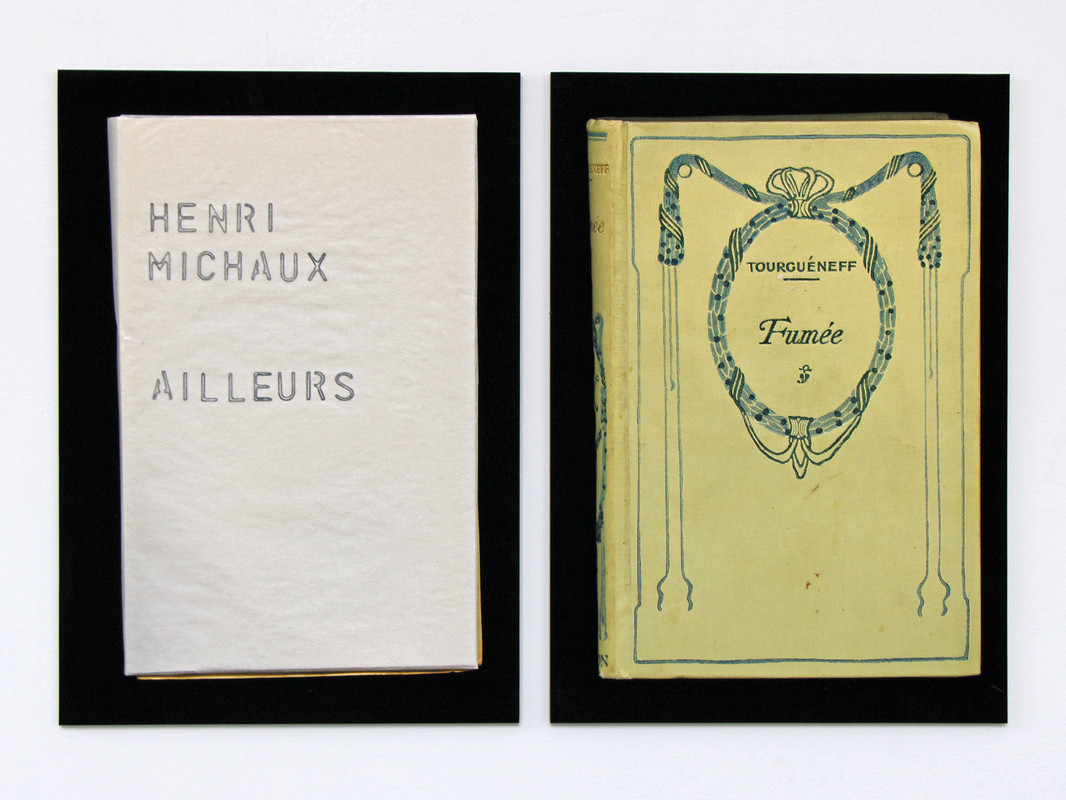

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Bibliothèque, 2023, Print on Hahnemühle paper mounted on panel, Ed. 5/5, each 42 x 29.7 cm

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Bibliothèque, 2023, Print on Hahnemühle paper mounted on panel, Ed. 5/5, each 42 x 29.7 cm

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Bibliothèque, 2023, Print on Hahnemühle paper mounted on panel, Ed. 5/5, each 42 x 29.7 cm

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Bibliothèque, 2023, Print on Hahnemühle paper mounted on panel, Ed. 5/5, each 42 x 29.7 cm

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Bibliothèque, 2023, Print on Hahnemühle paper mounted on panel, Ed. 5/5, each 42 x 29.7 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

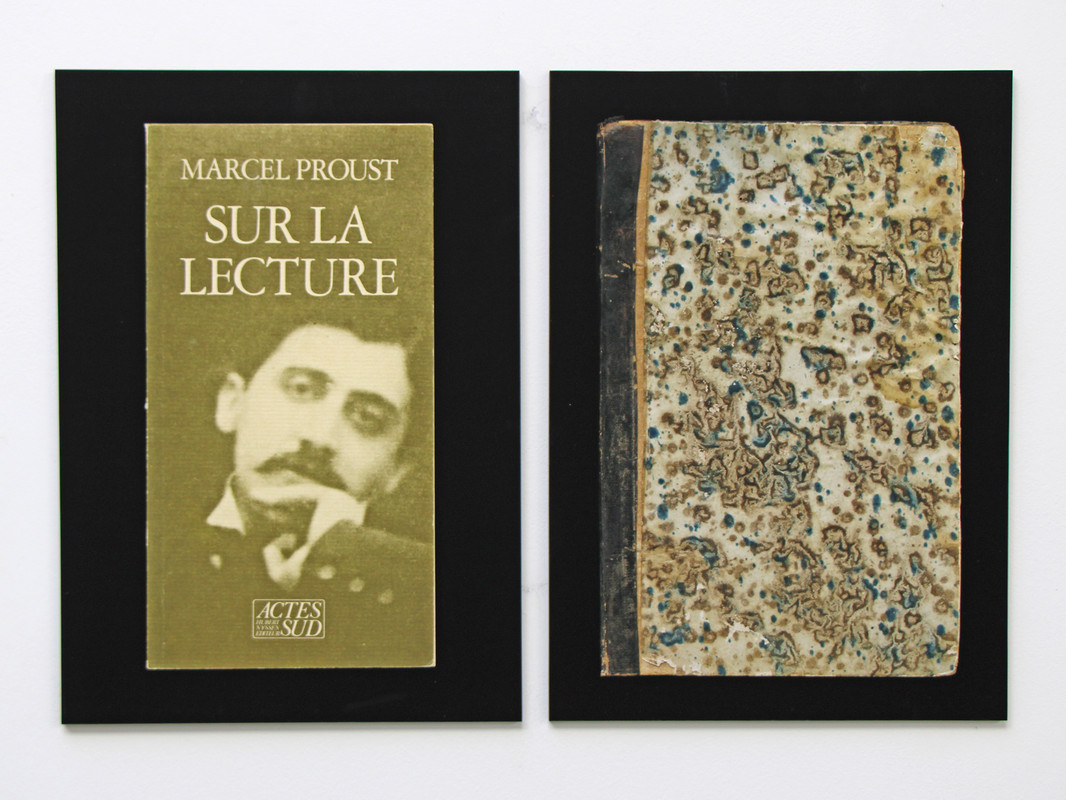

Hana Miletić, Materials, 2023, Crocheted and knotted textile (bright white organic cotton, organic cottolin, white latex-covered linen, and white paper yarn), 50 x 4 x 2 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

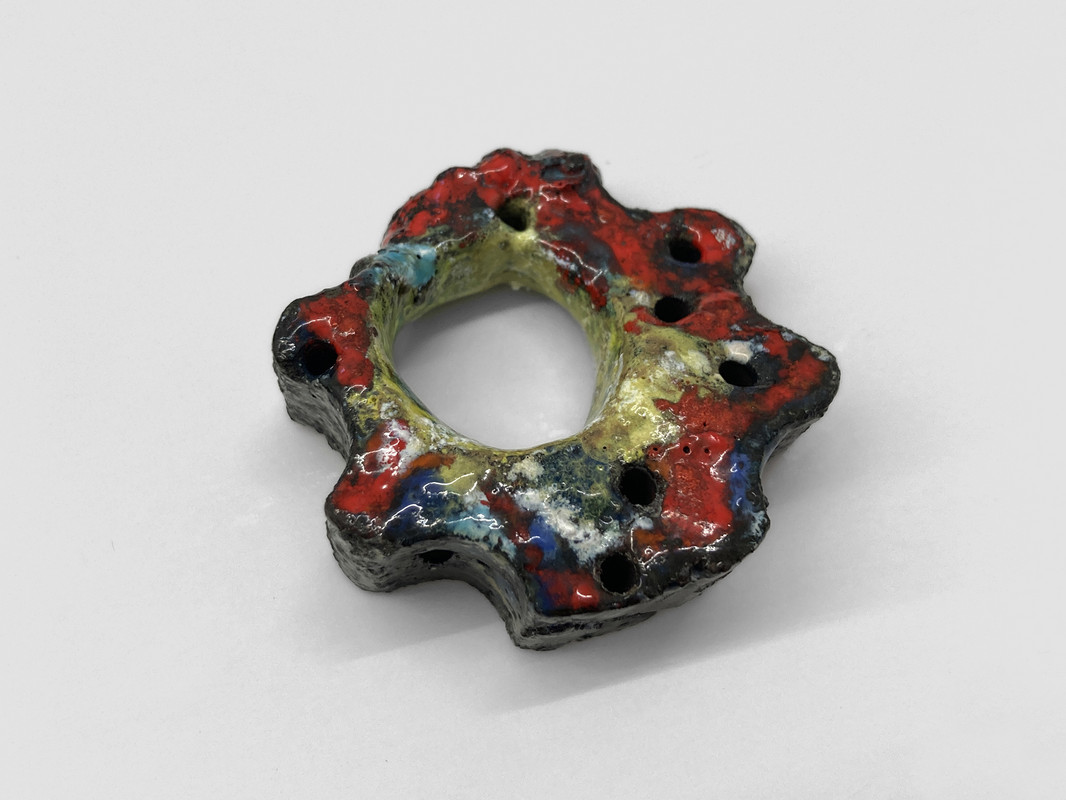

Ana Jotta, Tout passe, tout lasse, tout casse, 2024, Paperclay, glaze, Diameter 29 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Rochelle Feinstein, Dawned, 2022, Acrylic, acrylic enamel spray paint on cotton drop cloth, 130 x 130 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

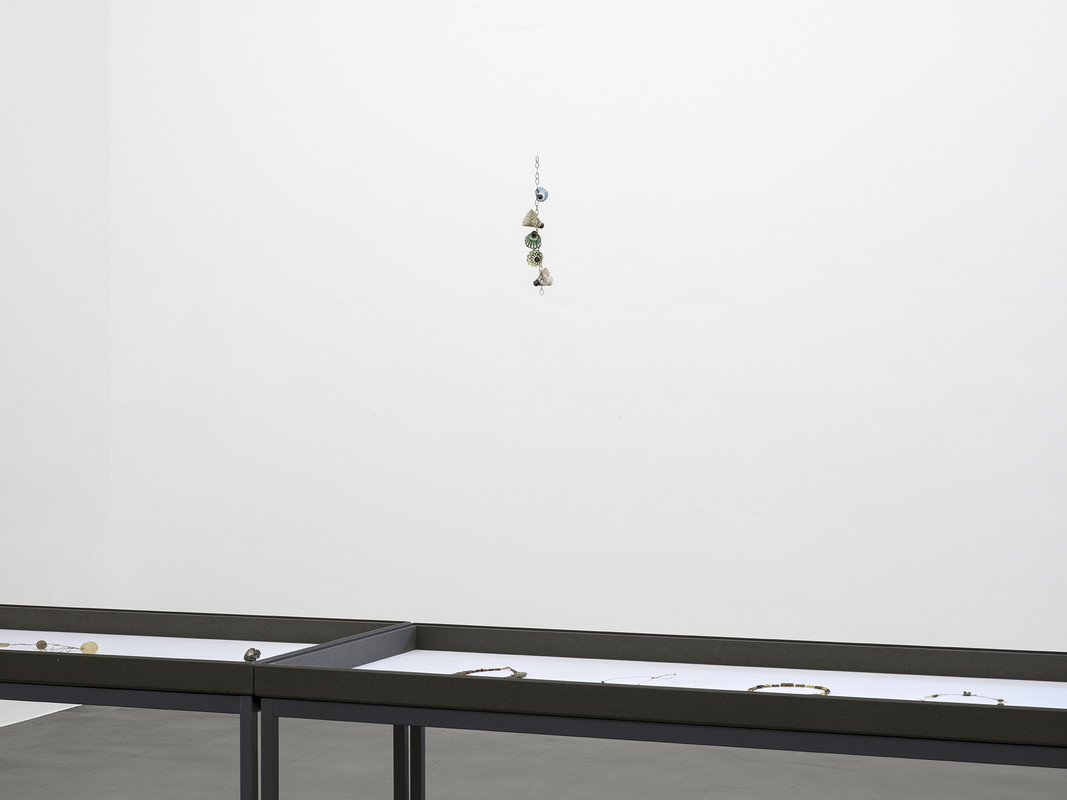

Isabelle Cornaro, (Composition) (detail), 2024, Objects in vitrine, mixed media, 88 x 190 cm

Jacqueline Mesmaeker, Couloir, 2021, Dry pastels and colored pencil on Japanese papers, 846 x 37.5 cm; 266 x 50 cm; 126 x 45 cm; 96 x 45 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Hana Miletić, Materials, 2022, Hand-woven textile (dark recycled jeans, indigo dyed organic cotton, recycled nylon, recycled plastic and white silk lap), 21 x 13 x 1.5 cm

Hana Miletić, Materials, 2023, Hand-woven textile (bright orange organic linen, recycled nylon, and recycled plastic), 400 cm, diameter 4 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

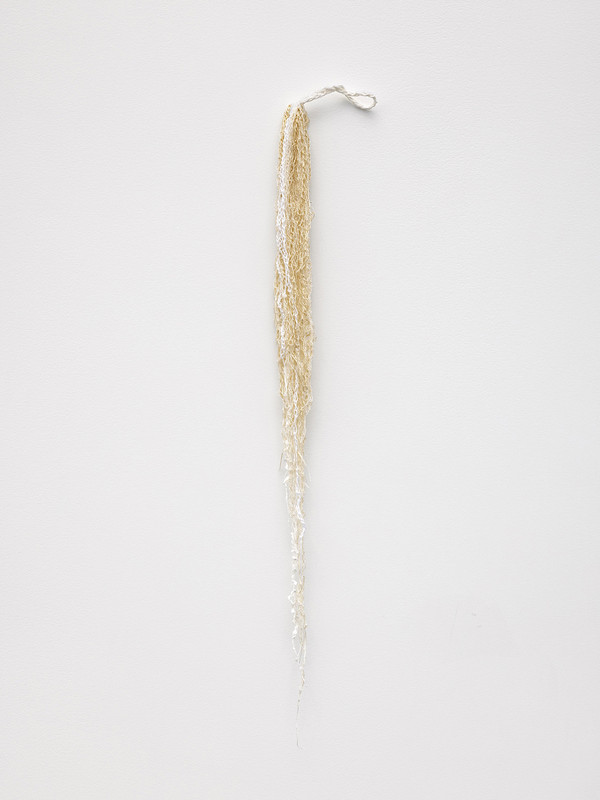

Katja Mater, Dare Note / Read On, 2021, 2 C-prints framed double sided, custom made frame, 33 x 24.3 cm, Ed. 1/3 (+ 1 AP)

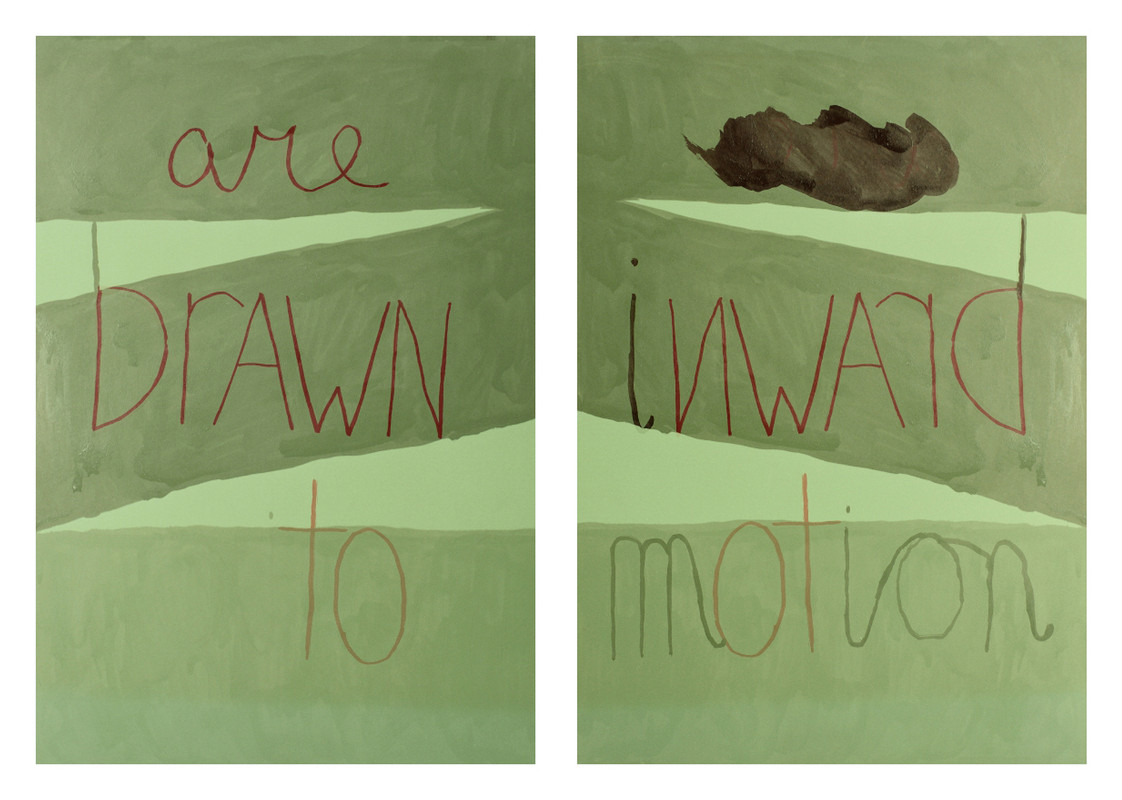

Katja Mater, Are Drawn To / Inward Motion, 2021, 2 C-prints framed double sided, custom made frame, 33 x 24.3 cm, Ed. 1/3 (+ 1 AP)

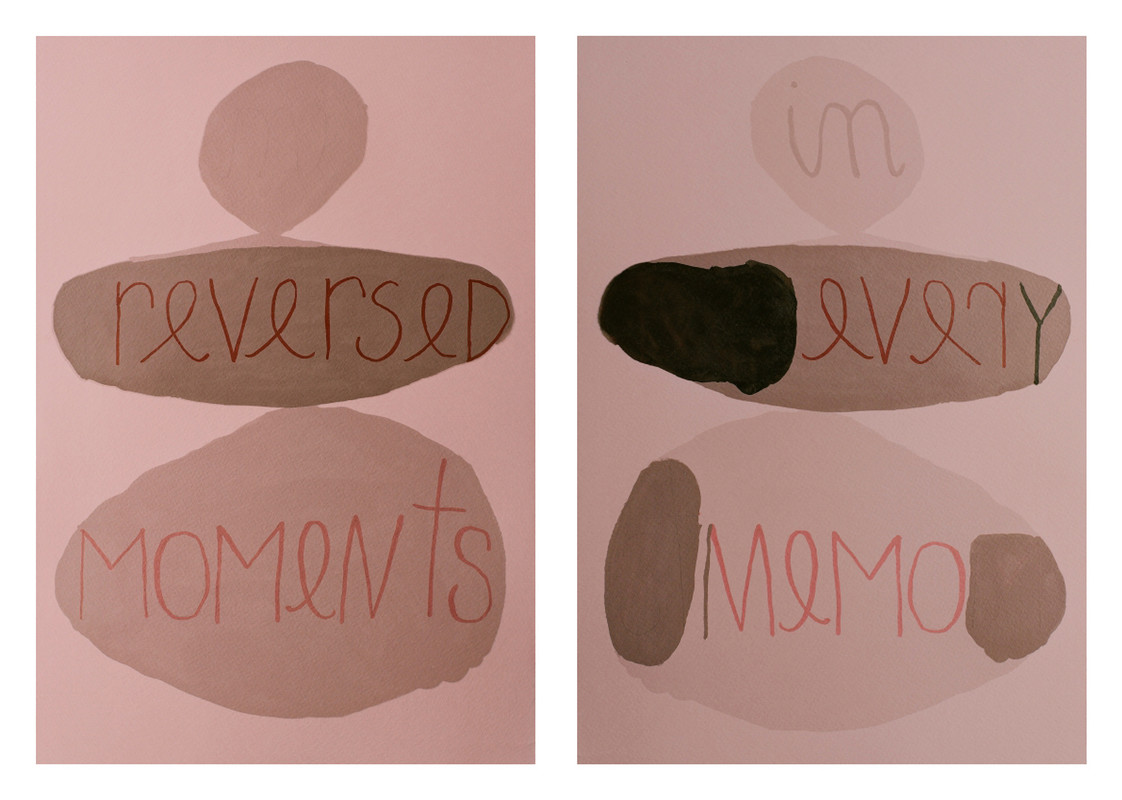

Katja Mater, Reversed Moments / In Every Memo, 2021, 2 C-prints framed double sided, custom made frame, 33 x 24.3 cm, Ed. 1/3 (+ 1 AP)

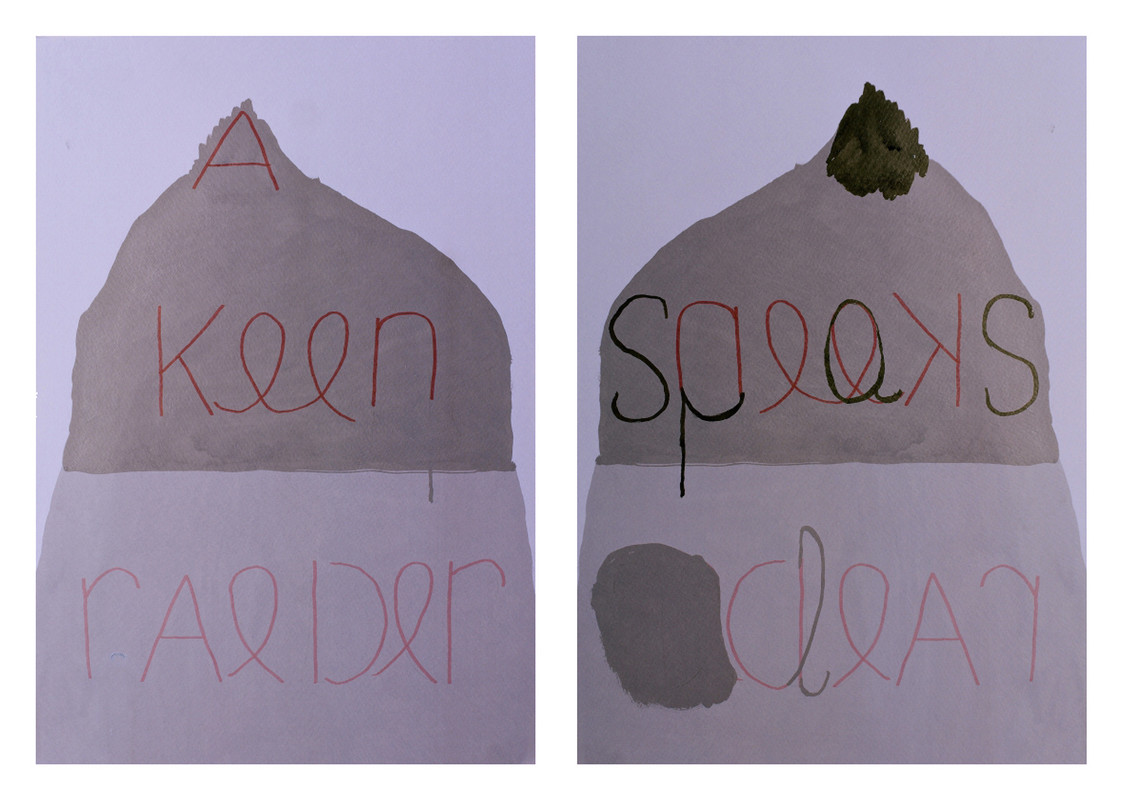

Katja Mater, A Keen Raeder / Speaks Clear, 2021, 2 C-prints framed double sided, custom made frame, 33 x 24.3 cm, Ed. 1/3 (+ 1 AP)

Rochelle Feinstein, Wonderful Weather, 2021, Oil on birch veneer, 83.8 x 83.8 cm

Installation view, Dietrich, curated by Anne Pontégnie, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

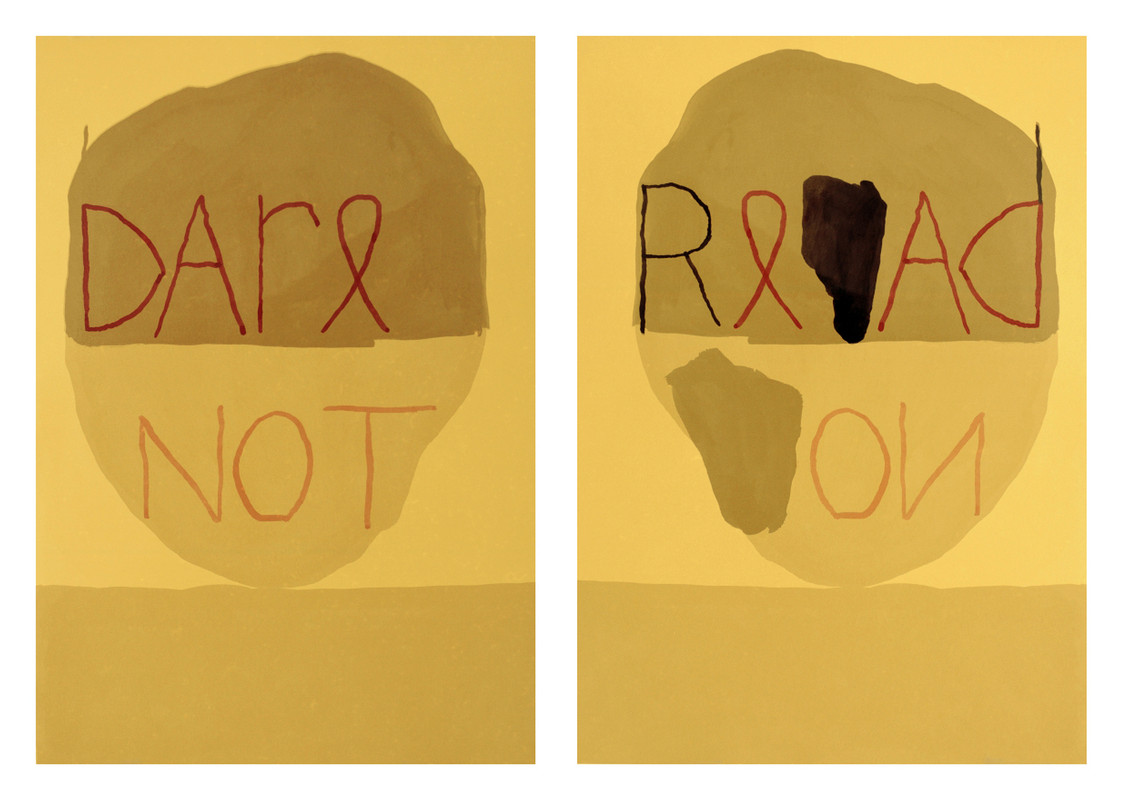

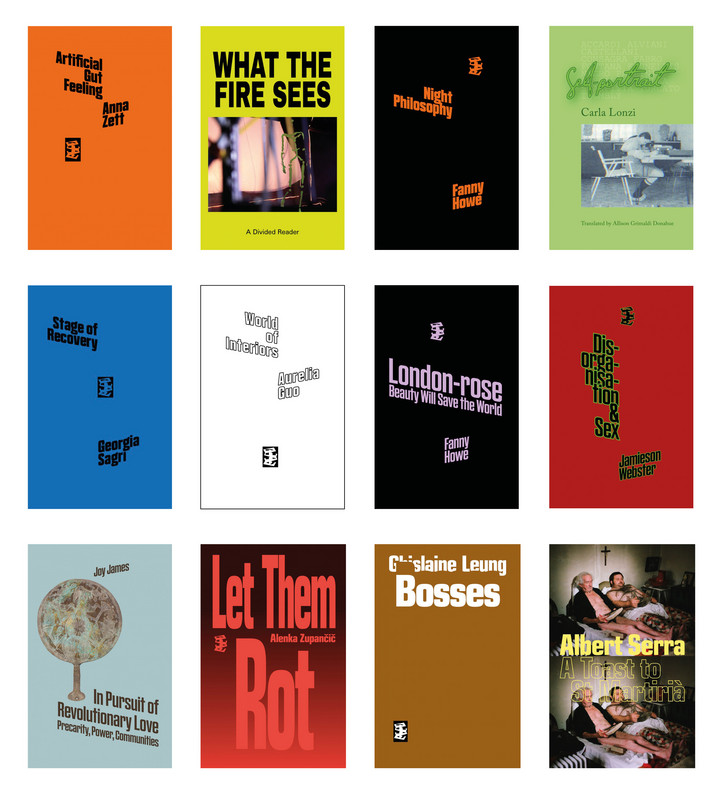

Eleanor Ivory Weber & Camilla Wills (Divided Publishing), Anna Zett, Artificial Gut Feeling; Fanny Howe, Night Philosophy; What the Fire Sees, A Divided Reader; Georgia Sagri, Stage of Recovery; Carla Lonzi, Self-portrait; Aurelia Guo, World of Interiors; Fanny Howe, London-rose | Beauty Will Save the World;, Jamieson Webster, Disorganisation & Sex; Joy James, In Pursuit of Revolutionary Love: Precarity, Power, Communities; Ghislaine Leung, Bosses; Alenka Zupančič, Let Them Rot; Albert Serra, A Toast to St Martirià, 2019–2024, Set of 12 books, each 21.6 x 13.9 cm

2024

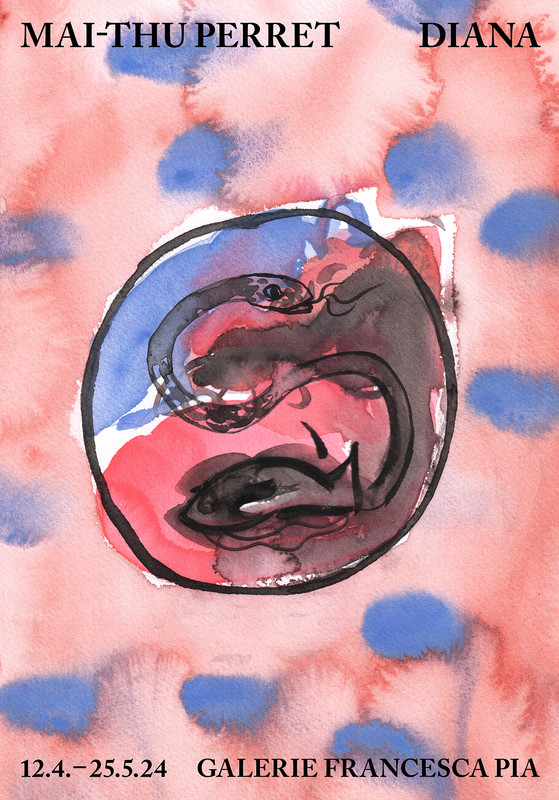

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana

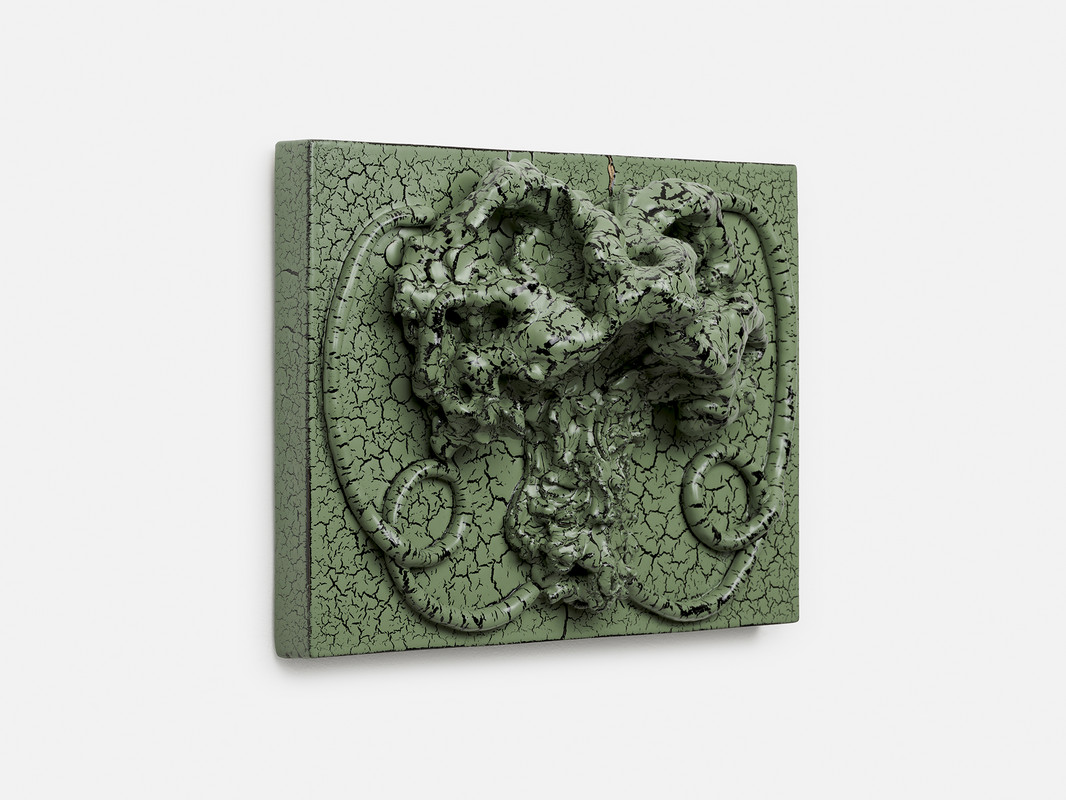

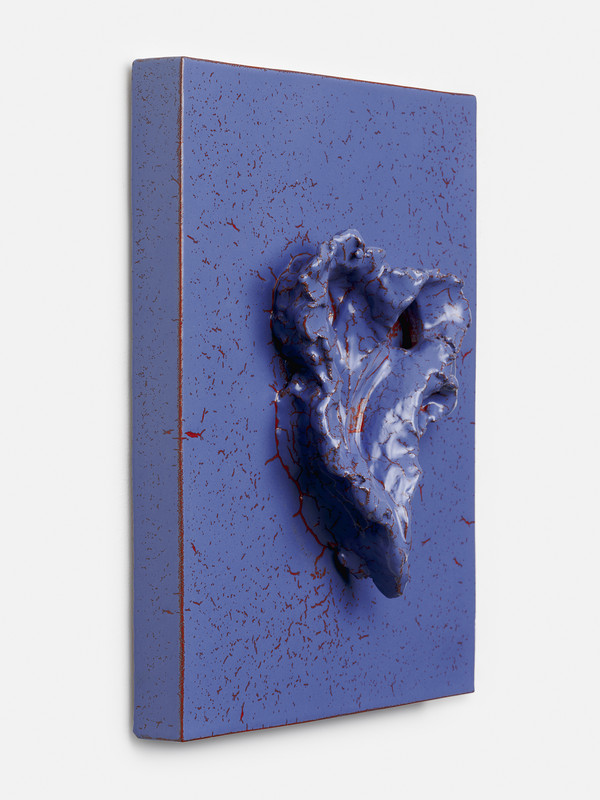

April 13 – May 25, 2024

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

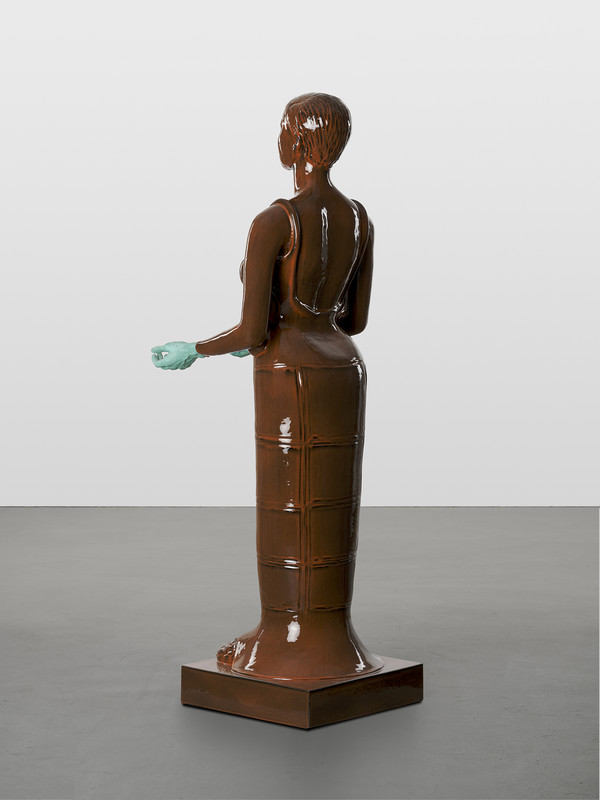

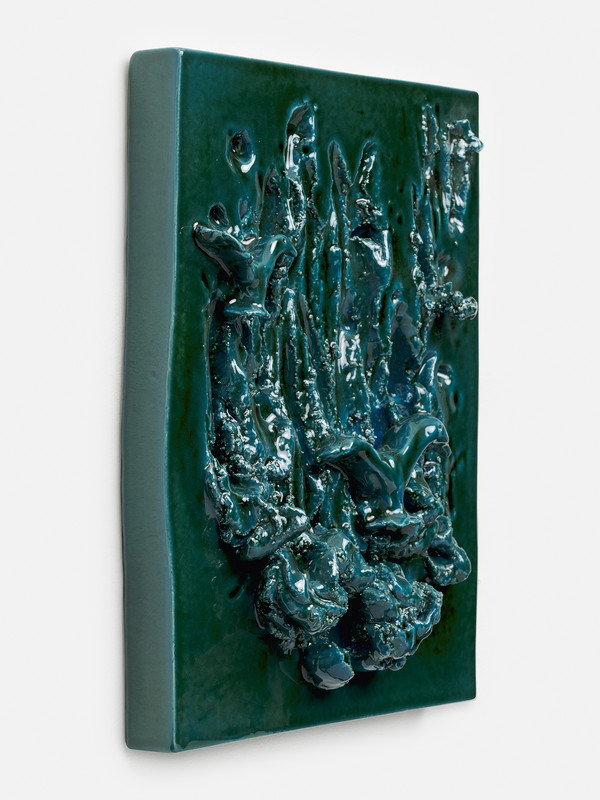

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II, 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II (detail), 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II (detail), 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II (detail), 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II, 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Diana II, 2024, Glazed ceramic, green bronze, 158 x 44 x 44 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

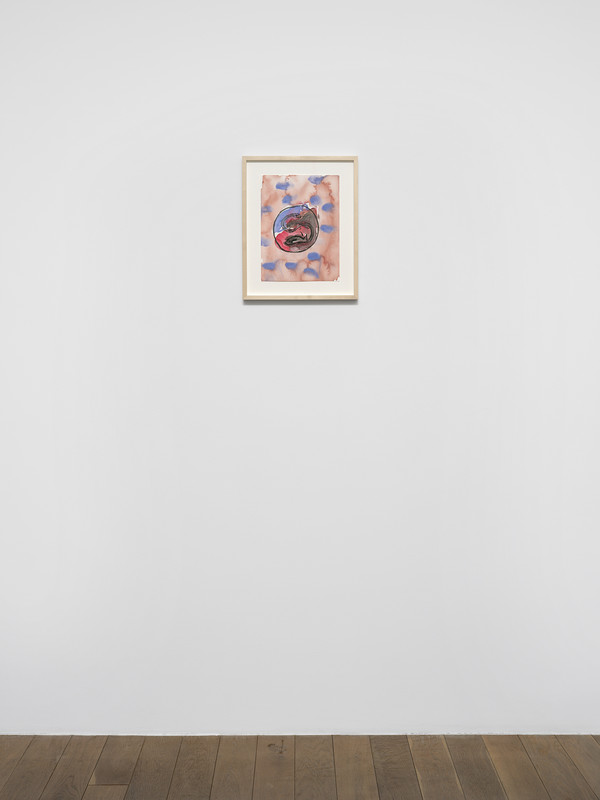

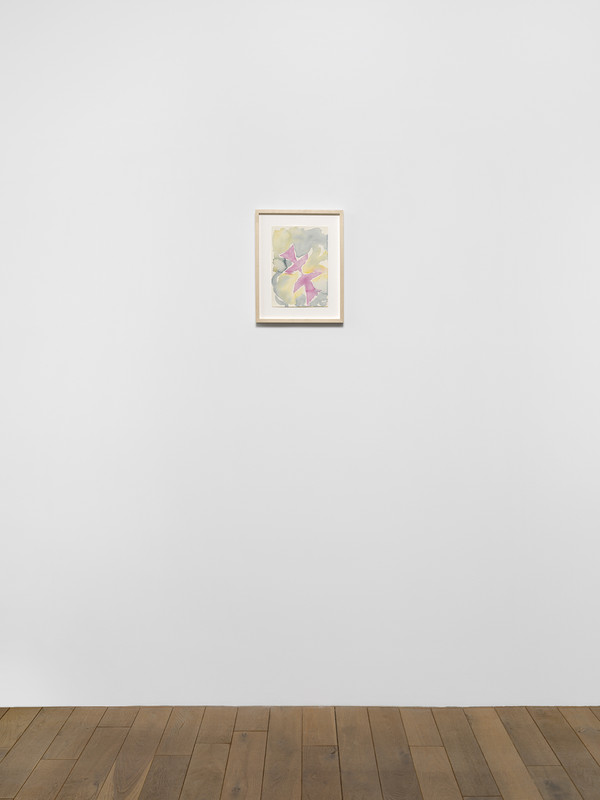

Mai-Thu Perret, Untitled, 2023, Watercolour on paper, 30.7 x 22.8 cm

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

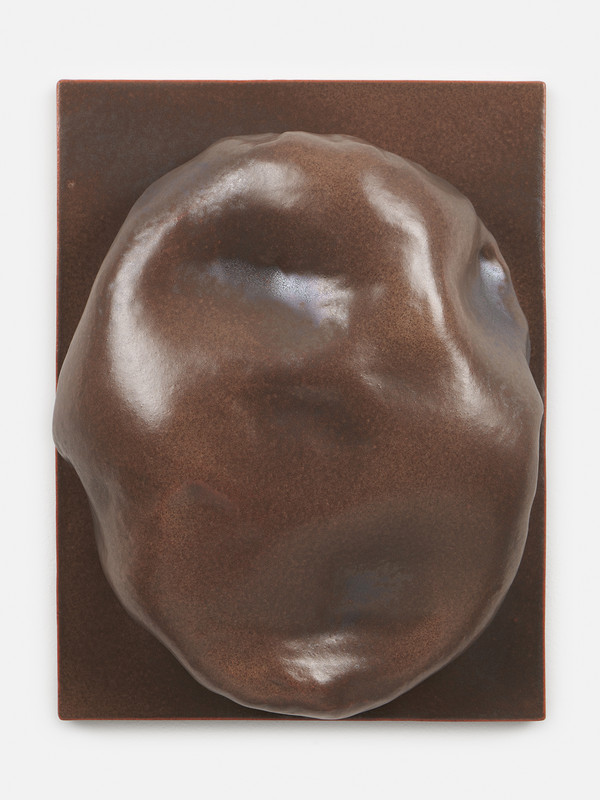

Mai-Thu Perret, The lion teaches the cub by making it lose its way, 2023, Glazed ceramic, 37 x 48.5 x 19 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, The lion teaches the cub by making it lose its way, 2023, Glazed ceramic, 37 x 48.5 x 19 cm, Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Carcinoplax Suruguensis, 2024, Bronze, Ed. of 5 (+ 1 AP), 6 x 30 x 18 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, Each time you bring it up it is new, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 54 x 25 x 24 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Each time you bring it up it is new, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 54 x 25 x 24 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Each time you bring it up it is new, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 54 x 25 x 24 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Each time you bring it up it is new, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 54 x 25 x 24 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Untitled, 2022, Watercolour on paper, 68 x 50.6 cm

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, Leftover soup, spoiled rice, not even dogs will look at them, 2022, Glazed ceramic, 48.5 x 37 x 16.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Leftover soup, spoiled rice, not even dogs will look at them, 2022, Glazed ceramic, 48.5 x 37 x 16.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, There is no voice by which to call it, there is no shape by which to see it, 2022, Glazed ceramic, 48 x 37 x 16.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, There is no voice by which to call it, there is no shape by which to see it, 2022, Glazed ceramic, 48 x 37 x 16.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, Serene and still, like springtime in the flowers, 2023, Glazed ceramic, 30 x 22.5 x 13 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Serene and still, like springtime in the flowers (detail), 2023, Glazed ceramic, 30 x 22.5 x 13 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, Untitled, 2022, Watercolour on paper, 70.9 x 50.8 cm

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, A single leaf flutters in the air and it’s autumn throughout the land, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 48.5 x 37 x 11.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Mai-Thu Perret, A single leaf flutters in the air and it’s autumn throughout the land, 2024, Glazed ceramic, 48.5 x 37 x 11.5 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

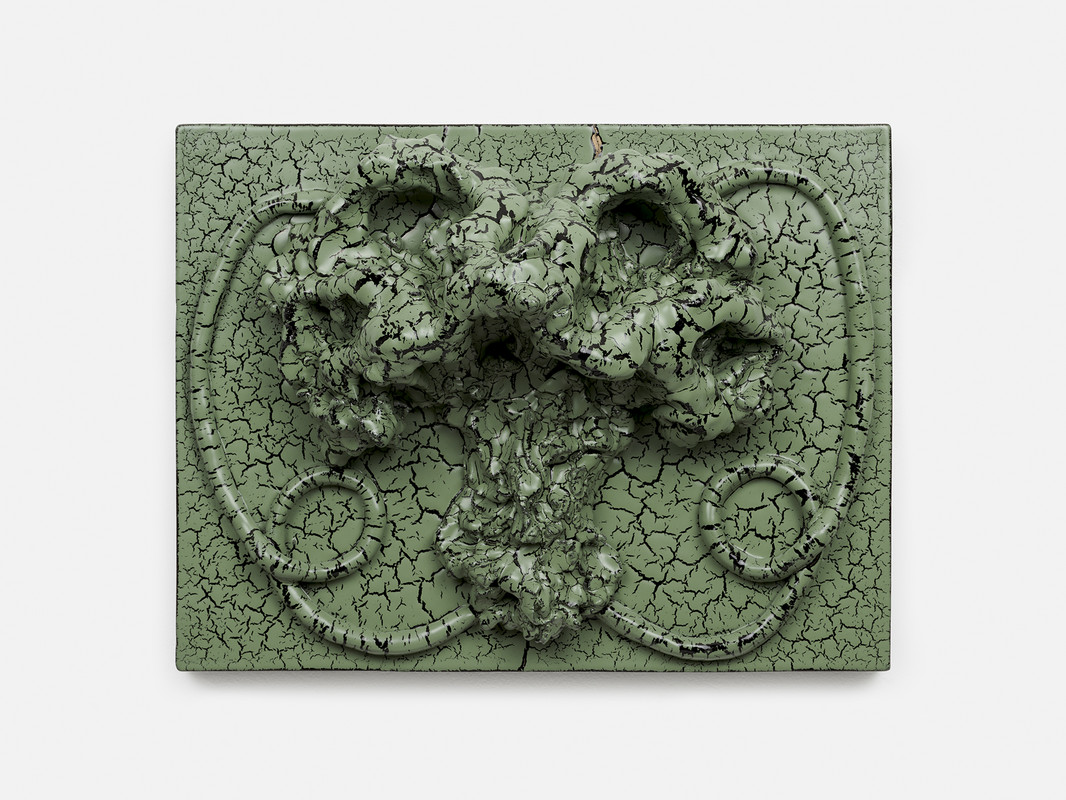

Mai-Thu Perret, The withered tree flowers in a spring beyond time II, 2021, Glazed ceramic, 72 x 55 x 7 cm. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, Untitled, 2023, Watercolour on paper, 27 x 18.9 cm

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

Mai-Thu Perret, Untitled, 2023, Watercolour on paper, 22.8 x 30.6 cm

Installation view, Mai-Thu Perret, Diana, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Annik Wetter

2024

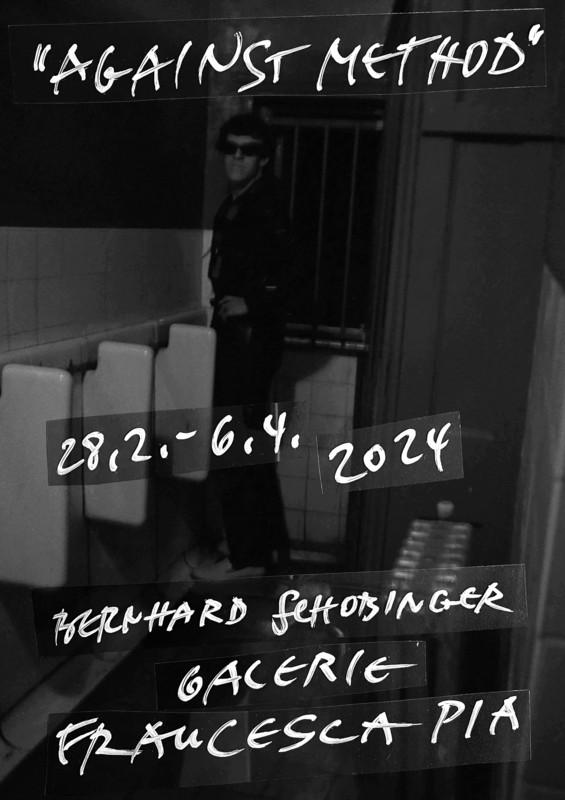

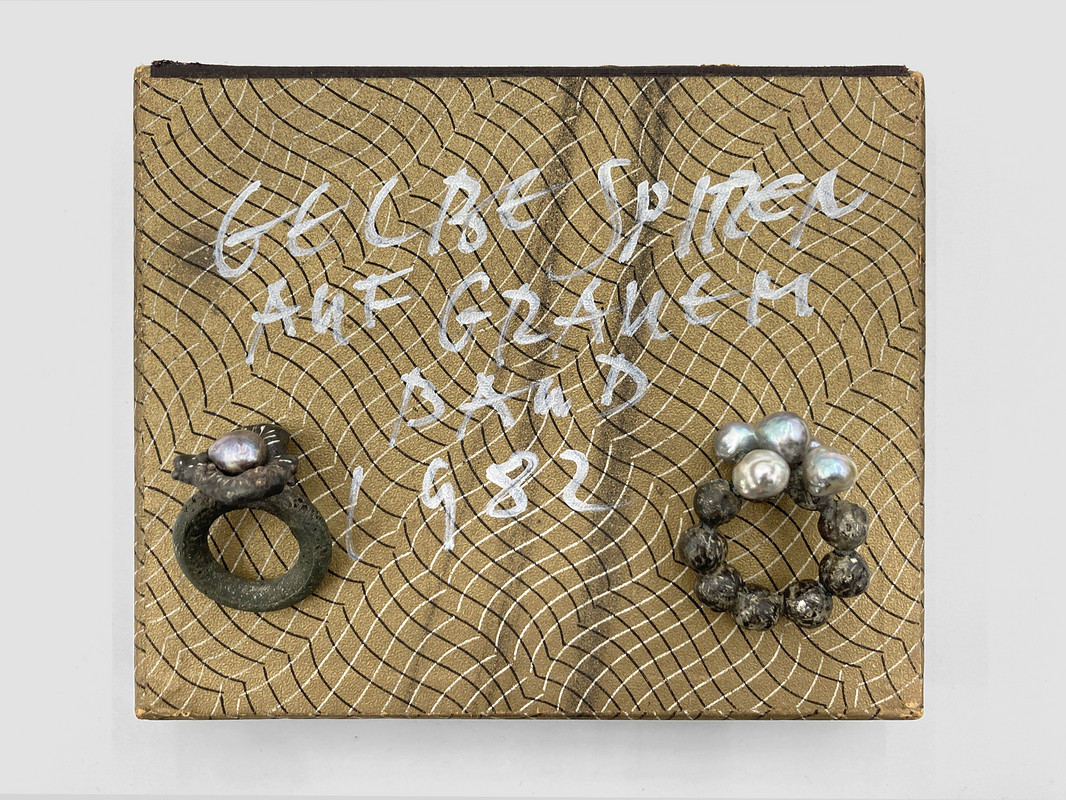

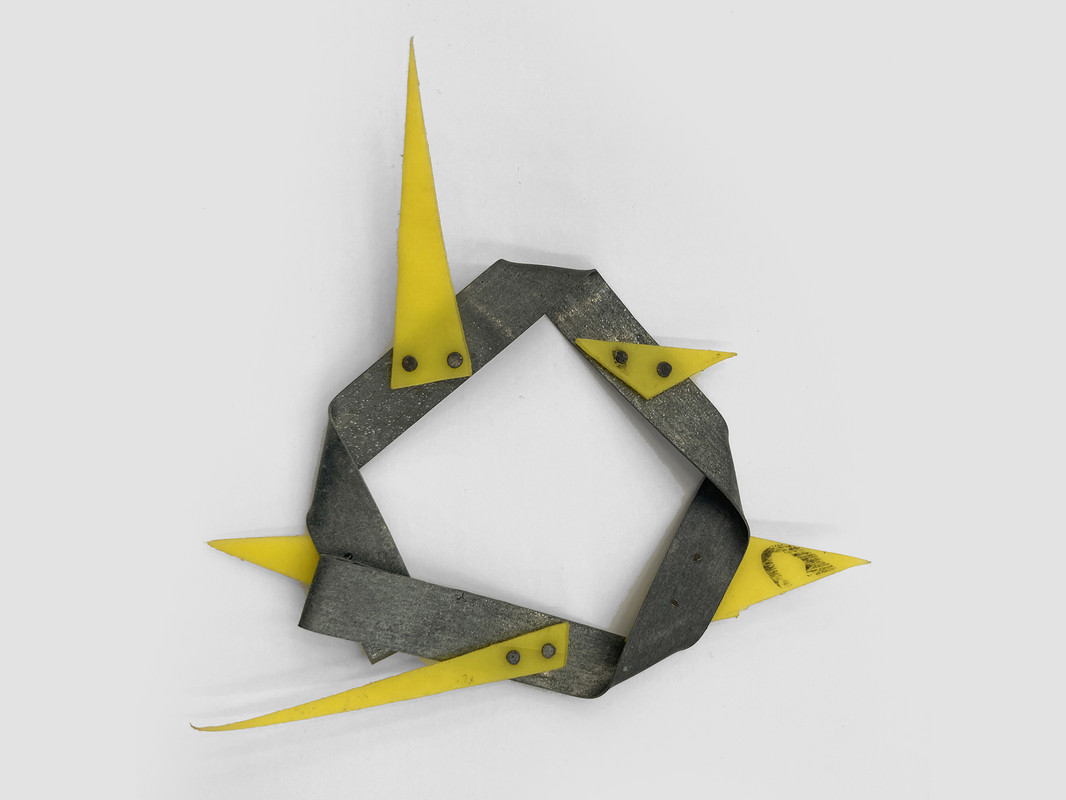

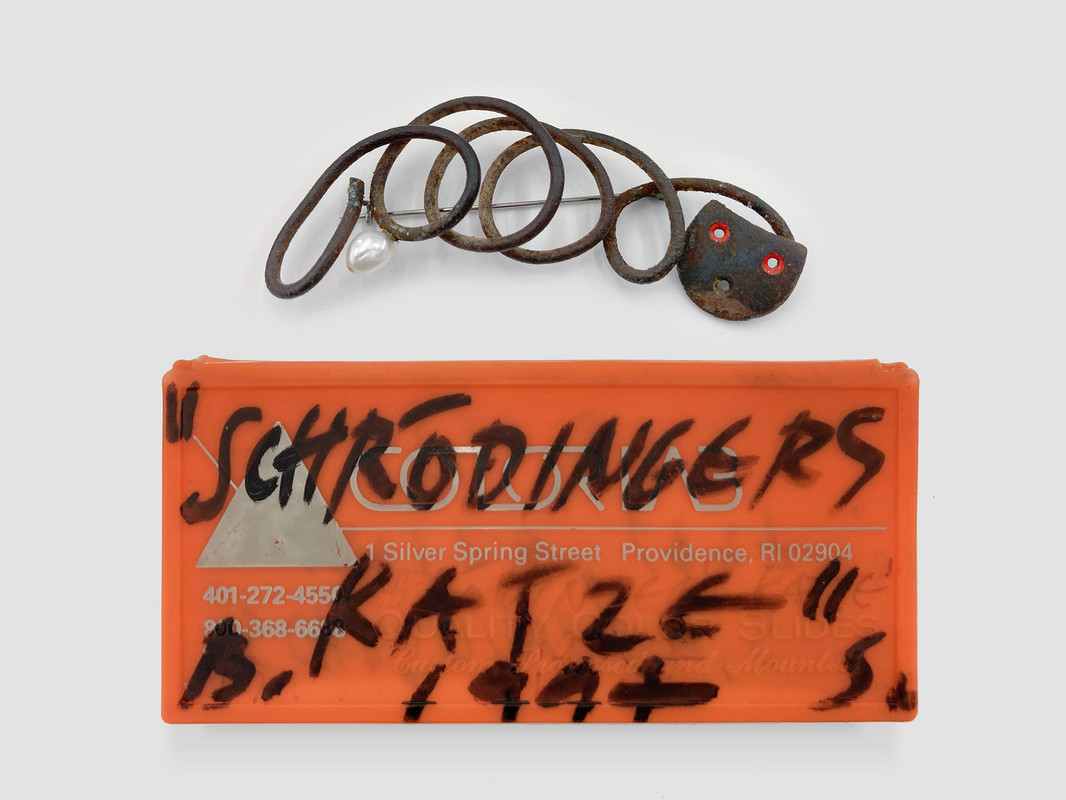

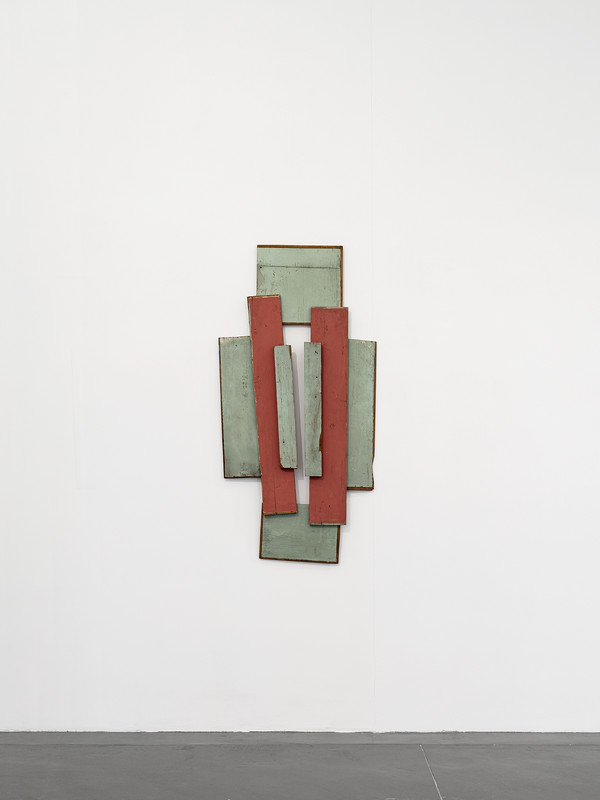

Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method

February 29 – April 6, 2024

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Sägen in der Höhe, 2024, Saw blades, bar clamps, approx. 100 x 150 x 140 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Dreiklang-Dimensionen, 2020, Necklace made of gold, amethyst, rock crystal, cobalt wire, 28.8 x 20.5 x 1.5 cm, Neckline 66 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Ring made of corroded clockwork, gold, 2.4 x 2.2 x 1.9 cm, Ring size 20, inner ⌀ 1.9 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Mutated Insect, 2023, Ring made of pearls, silver, cobalt, malachite pigment, 3.5 x 6.8 x 6.1 cm, Ringsize 17, inner ⌀ 1.8cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Insect Ring, 1993, Ring made of Shakudo (traditional Japanese metal alloy), turquoise, coral, horn, 2.6 x 3.2 x 2.2 cm, Ring size 15, inner ⌀ 1.7 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Cobalt Ring, 2012, Ring made of cobalt, Akoya pearl (Ise Shima), 3.7 x 2.9 x 2.6 cm, Ring size 13, inner ⌀ 1.6 cm; Untitled, n.d., Ring made of Akoja pearls (Ise Shima), silver, enamel, 4.2 x 3.5 x 2.3 cm, Ringsize 13, inner ⌀ 1.6 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Tutti Kabutti, 1980/1981, Necklace made of gold chain, plastic (objects found on a construction site), 23 x 10.7 x 2.5 cm, Neckline 46 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1983, Arm cuff made of titanium zinc, plastic, 12 x 12.4 x 1.7 cm, inner ⌀ 5.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Gummiring, 1980, Ring made of rubber, white gold, diamonds, 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.8 cm, Ring size 18, inner ⌀ 1.9 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Löffel-Brillen-Kette / Spoon-Glasses Necklace, 2013, Necklace made of silver, steel, glass, acrylic, 31 x 15.5 x 1.7 cm, Neckline 65 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Necklace made of thumbtacks, cobalt wire, 14 x 9 x 0.5 cm, Neckline 38 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Arm cuff made of gold-plated stainless steel, copper fitting, 6.5 x 6.5 x 1.4 cm, inner ⌀ 6.2 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Brooch made of two intertwined pieces of steel wire, paint, stainless steel pin, 4.2 x 11.5 x 1.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Vogel-Kette / Bird Necklace, 2020, Necklace made of iron, copper, paint, 8 tightening clamps for blinds, 62.5 x 25 x 1 cm, Neckline 123 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Schrödingers Katze / Schrödinger’s Cat, 1997, Brooch made of steel, steel heel-piece, enamel, freshwater pearl, 3.5 x 8.5 x 1.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 2006, Brooch made of antique jewellery, found spectacle frame, turquoise, pearl, enamel, gold, stainless steel wire, 1.8 x 12.3 x 1.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1988, Brooch made of coral beads, silver, chrome steel, 3.5 x 9.9 x 1.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Schwamm mit Perle / Sponge with Pearl, 2013, Brooch made of sponge, cobalt, Akoya pearl, 3.7 x 5.4 x 1.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1991, Brooch made of antique white gold rings, pearl, cobalt pin, 5 x 5 x 2 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1980–1984, Wood, paint, nails, 168 x 83 x 7 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 2023, Toy truck found underwater, smoky quartz, gold chain, 6 x 13 x 5.5 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Dezembermond / December Moon, 2007, Necklace made of porcelain, gold, malachite pigment, nylon string, 6.7 x 6.7 x 1.7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Wine Glass Stands, 2019, Necklace made of glass, red and gold urushi lacquer, silver, tourmaline, 20 x 23 x 2 cm, Neckline 44 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Shard Ring, 2009, Jugendstil monogrammed gold ring 18ct, glass shard from a Jugendstil vase, gold urushi lacquer, 3.6 x 2.1 x 3.7 cm, Ringsize 19, inner ⌀ 1.9 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Gift / Poison, 2011, Arm cuff made of glass (fragment from found bottle), red urushi lacquer, 7.4 x 7.6 x 3.8 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Fliegender Fisch / Flying Fish, 1980, Earring made of silver, glass, 11.2 x 5.2 x 0.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Poison Veleno Skulls, 2023, Bracelet made of gold, red urushi lacquer, half-pearls, glass fragments (from old bottles), 2.2 x 20.2 x 0.7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, R+B-Kette / R+B Necklace, 2014, Necklace made of rose quartz, sea glass (Okinawa, Japan), gold, 27 x 22 x 3 cm, Neckline 68 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Mind the Gap, 2015, Necklace made of agate, memory stick, hammerstone (stone age), red urushi lacquer, 30 x 9.5 x 4.5 cm, Neckline 52 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1995, Necklace made of wood, cowrie shells, string, 40.5 x 14.5 x 3.5 cm, Neckline 76 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Zeitsprung-Kette / Jump in Time Necklace, 2002, Necklace made of gold 750, Bang Chiang ceramic, marble, azurite, malachite pigment, 25.5 x 9 x 2.8 cm, Neckline 51 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Piano Peace, 2002, Necklace made of felt, ivory, string, metal keyhole, 57 x 11 x 2 cm, Neckline 104 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 1984–1985, Wood, paint, steel, 191 x 60 x 10 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Chinese Face I, 1984/1985, Wood panelling, paint, 150 x 180 x 7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Schnecken Ballett II / Ballet of Snails, 2020, Necklace made of shells (origin of Okinawa Island, Japan), malachite pigment, madder lacquer, shoelace, 30 x 30 x 8 cm, Neckline 68 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Juwelen-Türklinke / Jeweled Door Handle, 2002, Necklace made of diamonds, sapphires, rubies, emeralds, tansanites, metal door handle, japanese string, 68 x 15 x 1.5 cm, Neckline 108 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Plumber’s Beads, 1995, Necklace made of lignum vitae (light boxwood), hemp cord, 51 x 18 x 9.5 cm, Neckline 88 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Instabile Flächen, 1984, Wood, paint, 73 x 156 x 5 cm; Untitled, 1980, Plastic, 38 x 45.5 x 6.5 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Glacelöffel / Icecream Spoons, 1999, Arm cuff made of silver 925, enamel, 8.8 x 8.8 x 0.5 cm, inner ⌀ 6.3 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, 5 FR / 2 FR / 1 FR / 0,50 FR (1/2), 2023, Necklace made of silver (swiss coins), enamel, 15.7 x 15.3 x 0.2 cm, Neckline 41 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Trümmerring / Debris Ring, 2006, Ring made of silver, enamel, 5 x 4.3 x 3.5 cm, Ring size 14, inner ⌀ 1.6 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Kiku (Chrysantheme), 2022, Necklace made of silver (Japanese 1 sen coins), enamel, 17 x 17 x 0.3 cm, Neckline 47 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Pair of Bracelets, 1981, Arm cuffs made of silver 925, blue enamel, 9.5 x 9.5 x 1 cm, inner ⌀ 6 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Ring made of cast silver, enamel, 3.5 x 3.5 x 2.5 cm, Ring size 15, inner ⌀ 1.9 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Amöben-Ring / Amoeba Ring, 2015, Ring made of cast iron, enamel, 4 x 4.2 x 1.9 cm, Ring size 13, inner ⌀ 1.6 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Time Out, 2002, Ring made of stainless steel, diamond, enamel, 2.9 x 3.1 x 0.6 cm, Ring size 14, inner ⌀ 1.6 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Rotierendes Quadrat / Rotating Square, 2020, Arm cuff made of antique brass door handles, lapis lazuli pigment, 11 x 12 x 2 cm, inner ⌀ 7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Schmucklinie / Jewellery Line, 2002, Brooch made of a fragment of fountain pen from boarding school days, amethyst, gold 14 ct, silver, steel, plastic, 2 x 11.2 x 0.9 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Hacksilber-Collier / Hack-Silver-Collier, 1984, Necklace made of silver 800, 15 x 15 x 1 cm, Neckline 40 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, YES, 2010, Silver 800, 23.2 x 39.2 x 0.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Segmenten-Kette / Chain of Segments, n.d., Necklace made of silver 800, urushi lacquer, cobalt wire, 17.5 x 17.5 x 0.5 cm, Neckline 48 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Under Water Car Collection, 2023, Necklace made of metal, plastic, copper, silver, algae, 28 x 26 x 3.3 cm, Neckline 56 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Auto-Ring, 2023, Ring made of metal, pearls, gold 750, diamond, 2.8 x 2.2 x 5.5 cm, Ring size 15, inner ⌀ 2 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Edelstein-Kette / Jewels Necklace, 2009, Necklace made of 17 precious stones, cobalt wire, 20 x 9 x 0.3 cm, Neckline 44 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Cannonball Ring, 2010, Ring made of medieval cannonball iron (16th century), forged without joints, 2.6 x 2.3 x 1 cm, Ring size 16, inner ⌀ 1.7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Nagel-Ring / Nail Ring, 2011, Ring made of lemon citrine, white gold 750, 3 x 2.9 x 1.9 cm, Ring size 12, inner ⌀ 1.4 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Splinten-Kette / Cotter Pin Necklace, 1997, Necklace made of brass, precious stones, silver, 29.5 x 22.5 x 0.6 cm, Neckline 55 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Shuttlecock Necklace, 2023, Necklace made of cast silver, enamel, 48.5 x 6.5 x 6.5 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Variables Objekt, 1980–1984, Steel, wood, rigid foam, 141 x 33 x 13 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Antennen, 1984, Various metals, 147 x 40 x 25 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Bernhard Schobinger, Elektro Boogey, 1991, Necklace made of fine gold, stainless steel, electrical fittings, 20.3 x 18.7 x 0.7 cm, Neckline 50 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, 2020, Necklace made of brass and plastic keyhole fittings, cobalt wire, silver, 18.5 x 17 x 0.5 cm, Neckline 96 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Fischhaken / Fishing Hook, 2023, Necklace made of gold 750, garnet, amethyst, peridot, cultured pearls, coral, 25.5 x 15 x 1.5 cm, Neckline 50 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Eastern Crosses, 2023, Necklace made of antique crosses found in the Kievan Rus, bronze, copper, red corals, stainless steel wire, 22.5 x 19.5 x 0.5 cm, Neckline 56 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Pyrit-Ring, 2022, Ring made of silver 925, 3.5 x 3.9 x 1.8 cm, Ring size, inner ⌀ 1.7 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Untitled, n.d., Necklace made of smoky quartz, rock crystal, gold drawing on rock crystal, stainless steel, 54.5 x 13.5 x 3 cm, Neckline 114 cm

Bernhard Schobinger, Pyrit-Ring, 2022, Ring made of stainless steel, 3.5 x 3.5 x 1.7 cm, Ring size 13, inner ⌀ 1.7 cm

Installation view, Bernhard Schobinger, Against Method, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

2023

Emil Michael Klein

November 25, 2023 – February 17, 2024

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

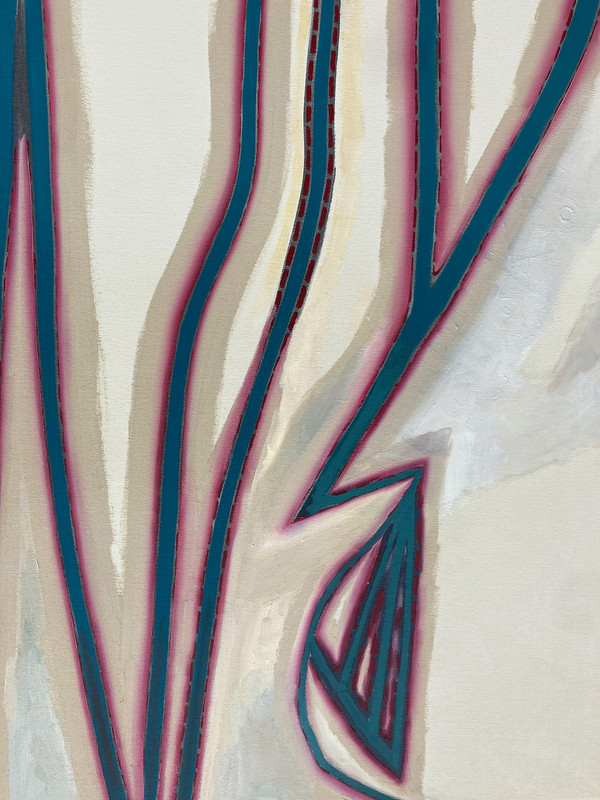

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 141.9 × 185.2 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 141.9 × 185.2 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 130 × 135.2 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 130 × 135.2 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 112.4 × 145.9 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 112.4 × 145.9 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 104.5 × 118.7 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 104.5 × 118.7 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 190 × 129.3 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 190 × 129.3 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 152.7 × 162.8 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 152.7 × 162.8 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 121.5 × 100 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 121.5 × 100 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 147.2 × 207.4 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 130 × 150 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 130 × 150 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled, 2023, Oil on canvas, 145.2 × 150 cm

Emil Michael Klein, Untitled (detail), 2023, Oil on canvas, 145.2 × 150 cm

Installation view, Emil Michael Klein, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2023. Photo: Cedric Mussano

back to top